What's this? A Book!

Or buy here: Light Publications, Powell's, or Bn, Amazon A look at the lousy situation Rhode Island is in, how we got here, and how we might be able to get out. Featuring

Now at bookstores near you, or buy it with the button above ($14, or $18 with shipping and sales tax). Contact information below if you'd like to schedule a book-related event, like a possibly entertaining talk on the book's subjects, featuring the famous mystery graph. Join the RIPR Mailing List! For a weekly column and (a few) other items of interest, click here or send an email to ripr-list-subscribe@whatcheer.net. RIPR is a (paper) newsletter and a weekly column appearing in ten of Rhode Island's finer newspapers. The goal is to look at local, state and federal policy issues that affect life here in the Ocean State, concentrating on action, not intentions or talk. If you'd like to help, please contribute an item, suggest an issue topic, or buy a subscription. If you can, buy two or three (subscribe here). Search this siteAvailable Back Issues:

Subscription information:

Contact:For those of you who can read english and understand it, the following is an email address you are welcome to use. If you are a web bot, we hope you can't understand it, and that's the point of writing it this way. editor at whatcheer dot net Archive:

AboutThe Rhode Island Policy Reporter is an independent news source that specializes in the technical issues of public policy that matter so much to all our lives, but that also tend not to be reported very well or even at all. The publication is owned and operated by Tom Sgouros, who has written all the text you'll find on this site, except for the articles with actual bylines. Responsibility: |

Sat, 31 Jan 2009

The Medicaid Waiver: Selling the Assembly

Imagine I've come to you with an idea for lowering heating bills in your house. "This amazing device will cut your heating bills by a quarter," I say. Naturally, you say, "What is this marvelous invention and how much does it cost?" And I reply, "I'm not sure about either, really, but we'll figure out something. No one will get hurt, and you know you can trust me because I'm wearing a nice suit. Did I mention it will cut your heating bills by a quarter? Sign here." Would you sign or send me packing?

If you were the leadership in the General Assembly -- House Speaker William Murphy and his team -- you'd sign. Yup, knowing almost none of the important details, those hard-boiled realists happily bought the assurances from Governor Carcieri and Gary Alexander, his director of Human Services, that the Medicaid "global waiver" under consideration is a good idea. What's more, they bought it in a highly undemocratic fashion: the Speaker simply declined to schedule a vote on the subject, and under the terms set last year, it goes into effect automatically. Legislators who object to this fiasco have had no opportunity to do so since the idea was sprung on them in a surprise budget amendment last June.

To his credit, Representative Steven Costantino, chair of the House Finance committee, had some pointed questions for administration witnesses last week, and last year when the waiver was first heard. He clearly understands the risks involved. However, he and the rest of the leadership must understand that ringing defenses in the hearing rooms, or penetrating and hostile questioning of administration witnesses are nothing but show if the result is that terrible policies are enacted. Make no mistake, the only way to pay for what the Governor says he intends to do for the state's long-term care population is to devastate the medical care provided to the state's poor population. (For those keeping score, RIte Care is more than two-thirds of our Medicaid patients, but only a fifth of the costs.)

The stated intent of the waiver -- letting long-term patients choose less expensive home care over institutional care -- is a good thing. Many people will be glad to have that alternative, which they haven't had before. But it's simply not realistic to think these changes are going to cut $67 million from the Medicaid budget in only a few months. To put it in perspective, this is around 10% of our annual expense for long-term care. Home care is cheaper, but it's not magic. Potential savings are in the neighborhood of 35% per patient, according to studies I've seen. There are between 7,500 -- 8,500 people in nursing homes. To get 10% savings this year from that population alone would require moving around 2,000 people from institutional care to home care between now and, say, next week. And where will the home care workers come from? The visiting nurses and other suppliers say they don't know. People have to be hired and trained, and that doesn't happen overnight. The whole proposition is absurd.

Under the terms of the global waiver, because it's "global", money can be transferred from RIte Care -- medical care for the poor -- to nursing homes and elder care. Because it can be transferred, it will, because we'll be broke.

RIte Care has been under seige for a while. In recent years, co-pays have gone up and eligibility rules have been tightened. And there have been other, more subtle attacks on the quality of care. For example, starting February 1, a rule is going into place to forbid RIte Care doctors from prescribing anything but generic medication. Generic medications aren't a bad idea, but it takes a fair amount of time for good drug ideas to appear as generics, and some drugs never do. The result? Doctors for the poor won't be able to prescribe what they think best for their patients. In a world of limits, we're not going to be able to fund all treatments, but we're not talking about heroic end-of-life measures here. For example, some of the most effective medicines for kids with ADHD have no generic version, and there are plenty more like that.

It's a bit unclear whether this change is part of the anticipated Medicaid savings, but there's a push to modify this rule to allow some non-generic medications. I'm glad to hear it, but what of the budget? The Assembly is on record approving the budget; who are they to complain about the details?

House Finance is currently reviewing a bill to demand oversight of the changes the Governor would make to Medicaid. But this is an empty gesture, like shaking your fist at the burglar after he's run away with your money. About the only thing the Assembly can do now is demand that the Governor not achieve the cost savings he intends. If they know how to get the cost savings, they should have put that in the budget. If they don't believe the cost savings he intends will be good for the state, they shouldn't have passed the waiver in the first place.

To allow the savings from the waiver into their budget, and then to demand that it be done in a way that won't achieve the savings is, well, it's not a sound way to conduct your state's business, is it?

Finally, let's remember that RIte Care is a program designed to save money. Poor people get sick whether they have affordable health insurance or not. If they don't, they wind up seeking help at hospital emergency rooms, where they get it at great expense. Or they don't get it, and die, and that ruins the feng shui of our cities. RIte Care has been a very successful program -- it has saved us money -- letting the program decay will be expensive in the long term, even if it saves us some dollars this spring.

12:22 - 31 Jan 2009 [/y9/cols]

In fact, around 11% of people don't, according to a study by the NYU law school and the Brennan Center. Find it here.

09:50 - 31 Jan 2009 [/y9/ja]

Mon, 26 Jan 2009

Last week, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement Service terminated its contract with the Donald W. Wyatt Detention Facility in Central Falls, part of the continuing fallout over the death last summer of Hiu Lui Ng, a Chinese computer engineer who had overstayed his visa and was in detention there. This is as good a time as any to review history of the Wyatt jail. But first, a word about the real-world meaning of sophisticated economics abstractions.

A few months ago, I had to buy a new stove. The event gave me an opportunity to reflect on the phenomenon of productivity. This is the amount of goods or services a company provides divided by the cost of making it. Increasing productivity is a grand-sounding economics abstraction that conjures up images of marvelous robots and complicated machines that automatically weld each metal panel onto my stove, along with the logistics advances and Just-in-Time inventory controls that cut warehouse expenses. Not only does it sound grand, but doesn't it do your heart good to know that American productivity growth over the past 10 years was double the two decades before? Picture with me the armies of efficiency experts, manufacturing engineers and computer programmers who made possible this revolution in manufacturing. Marvelous, no?

But technically speaking, increases in productivity don't just mean assembly-line robots. They also explain why my stove's bottom drawer is a flimsy and nearly useless piece of junk that already jumps its rails as a matter of course. Whoever it was who figured out how to make a stove drawer out of plastic and what seems like tinfoil increased productivity just as much as the engineers who figured out how to assemble it efficiently. That is, there are good and bad ways to increase productivity. The market is supposed to be the arbiter of which ways remain in use, but in a market driven by price, quality will always be driven to the ragged edge of adequate. (Or beyond -- since when is a sled a disposable item?)

So now consider prisons. Ideas for increasing productivity have been lurking about since Jeremy Bentham developed his "panopticon" design in 1785. His idea was that by laying out the cells properly, one guard could see all of them, and adequately guard many more prisoners than in a prison of a more traditional design. That's a useful insight, and lots of prisons are built to incorporate some of these ideas now.

But another way to increase productivity is just to skimp on training your guards, pay them poorly, be stingy with inmate medical care, and buy cheap food, too. Unlike my stove drawer, though, people's lives are put at risk by these kinds of productivity increases, and last summer, Mr. Ng died, reportedly due to a lack of necessary medical care. Here's the best part: this is a completely predictable outcome. Once private companies start competing for business, in an environment where price rules, you can count on the service eventually to settle to the level of barely adequate, if that. What's more, to advocates of privatizing services, that's the whole point.

There are some forms of increasing productivity that are utterly inappropriate for public services, because lives are at stake. It is not unreasonable to prefer quality over price in public services. Why? Because I want the people who teach my children to be the best available, and because I want the people who put out the fire in my house to be that way, too. I want our insurance regulators and the public health technicians and the people who look after the health of our Bay to be the sharpest we can get, too. And the rest.

Ours is the politics of polarization, and as part of that, calling for quality public services is routinely portrayed as being a tool of public employee unions. But this is profoundly, well, dumb, the perspective of people to whom cost is not just everything, it's the only thing. The fate of Mr.Ng tells us they could hardly be more wrong. Having quality services doesn't mean capitulating to public employee unions. I want my government to bargain hard, but in good faith. But I also want them to acknowledge that cost is important, but low cost is not always the highest good.

Another dirty little secret privatizers won't mention is that you often don't even get the low costs. On the other side of the coin, we have, just for example, Northrop Grumman, the private contractor who maintains the computer system that we use to pay food stamps and welfare checks. The state doesn't have the expertise to do their job -- and chose not to acquire it as a matter of policy -- so we're on the hook to them for $5 million every year, and there's not a blessed thing we can do about it without investing serious money to rewrite the system.

Wyatt was built in 1993, part of generational movement to privatize services traditionally supplied by government. It was supposed to be that magic "win-win" with investor profits, payments and jobs for Central Falls, and cheap rates besides. (Yes, and I'd like to talk to you about some magic beans I have for sale.) Now we see the truth: the salesmen sold us unsafe conditions, few jobs or money for the city, but comfortable profits for them. Over the first few years, investors earned over 9% returns, including a windfall one year of around 28% when the city refinanced some of the Wyatt bonds. They earn income per prisoner, and also by raking off the cost of phone calls, something the state prisons aren't allowed to do. With any luck, the privatizing wave is about to pass us by, because while it has saved us some money here and there, it has too frequently become a source of profits for a very few and expense, embarrassment, and disgrace for the rest of us.

00:29 - 26 Jan 2009 [/y9/cols]

Fri, 16 Jan 2009

Last week we saw Governor Carcieri unveil his plan for solving the state's budget nightware. There are some good ideas in it: reforming long-term care for the disabled and elderly, increasing the size of the state's health insurance purchasing pool and relieving some of the unnecessary legal burdens on cities and towns. These are important changes, and I wish they'd been undertaken years ago, but these weren't the meat of the matter. Unfortunately.

In his speech, Carcieri said our state "faced difficult choices." Unfortunately, he chose the easy way on every single one of those choices. What's so difficult about that? He would have us balance our budget by throwing poor people, state employees and cities and towns under the bus. Better now than in a few weeks. After RIPTA makes its schedule cuts at the end of January, it will be hard to find a bus.

He closed this way: "The decisions I have outlined here tonight balance our budget without raising broad-based taxes, without removing the safety net from anyone in need, and without putting anyone out of a job." It sounds good, even stirring, but not a word of it is true.

To begin with, it doesn't even balance the budget. The only way he gets to balance is by putting off some big payments (like the Station fire settlement) into 2010, "selling" some state land to RI Housing, a state agency, and praying the federal government will raise the Medicaid match by 3 percentage points in a couple of weeks.

Number two, "broad-based taxes." He's proposing to cut more than $122 million from the budgets of cities and towns, in the current fiscal year. It's not at all clear how the towns will get through the year short 4% of their budgets, but state property tax limits don't apply to towns who have to make up for cuts in state aid, so many will respond by increasing their property tax rates in the coming year.

Number three, what about the "safety net"? After months of inadequate explanations, it's still hard to see how the Medicaid waiver saves us any money this year without dramatically tightening eligibility rules or reimbursements in RIte Care. All of the good things he promises about changing the way we deliver long-term care could have been achieved without a waiver so broad. The Governor continues to claim it's all a good thing and will result in better care for less money, but he and the head of DHS are still the only people who don't wonder how.

Which brings us to number four, that no one is put out of a job. How does he imagine the towns will make up $122 million if not with layoffs? For example, he proposes cutting the requirement for school bus monitors. Does he imagine that school committees -- without the money or the legal requirement -- will simply keep these employees on out of the goodness of their hearts?

But more important than the individual parts is the central fraud, that we can cut costs by this huge amount, and you and I won't feel it. What government program has he said he will cut? None. Here's why that's important. Having six people in an office that had 20 last summer and who are completely swamped and unable to be effective at their jobs is a waste of money.

Have you wondered where the waste is in government? It's right there in front of your eyes, in transportation departments that can't afford to maintain our roads, in environmental protection departments that can't do timely reviews of the permits in front of them, in child protection services that put the state at serious risk of having a child die in its "care" and all the rest. Trying to run programs like these on a shoestring isn't a terrible idea -- being economical is a good thing -- but only if we're honest when the shoestring breaks. Otherwise, government becomes more expensive and less effective, pretty much what we've achieved under this governor.

The budget proposal does address the revenue side of the equation. But is it really fair to raise cigarette taxes by a dollar a pack while giving a few thousand families a tax cut worth thousands of dollars apiece. Yes, that's right, during the budget address, the Governor repeatedly mentioned that he was going to get us out of this without raising broad-based taxes. Mentioned nowhere was that this is year three of a five-year plan to cut the taxes of the richest 14,000 taxpayers in the state, estimated to cost the state at least $35 million this year. As of a few days ago, on January 1, if you earn more than around $300,000, your income taxes went down by as much as 7%. If you take home $500,000 a year, you'll keep an extra $2,500 this year, which will more than cover the property tax increase you'll see.

The worst part of all this is that the Governor has us perfectly positioned to absorb and neutralize most of the good a federal stimulus package might do. Paul Krugman wrote a couple of weeks ago about the danger posed by "50 little Hoovers" contracting their local state economies even while the federal government is poised to add stimulus. The deflationary effects of Governor Carcieri's budgets will offset a huge chunk of whatever stimulus is sent our way.

So there's the wrap-up: the Governor relies on one-year gimmicks and stiffing poor people, unions and municipal government to get through one more year. In return, we get an ineffectual but still expensive government, and we get devastating and deflationary cutbacks virtually guaranteed to neutralize much of the help we might get from Washington. The legislature will do well to lose this embarrassing proposal and write something new. Sadly, the difficult decisions are now theirs to make, and we know how good they are at that kind of thing.

22:35 - 16 Jan 2009 [/y9/cols]

Sat, 10 Jan 2009

This is good:

Some folks, of course, will oppose the Stark plan because they’re right-wingers who don’t want to expand health care coverage. And some folks, will want to focus their energies on other, worse, plans because those plans have a better chance of passing. But what’s incredibly frustrating is that a lot of people who claim to want to change public policy to expand health care coverage and better control health care costs will nonetheless fail to embrace Stark’s plan or anything similar for no real reason other than ideological posturing. It just can’t be the case, as a matter of centrist dogma, that the best solution is actually the most left-wing solution. It’s a far more ideological stance than anything you’ll ever hear from Pete Stark or from me. But the people hewing to it will insist on being called pragmatists.

23:14 - 10 Jan 2009 [/y9/ja]

An article in the New York Times a couple of weeks ago drew heavily on the irony that the private Donald Wyatt jail in Central Falls relies heavily for its income on the Department of Homeland Security. DHS places arrested illegal immigrants there, many of whom have recently been arrested -- in Central Falls. The irony is rich and the human cost of the arrests combined with the insanely opaque immigration bureaucracy is tragic, but what of the big story? Illegal immigration is constantly in the news, but why is it so hard to find a solution?

Solution? Maybe it's best to ask first, what is the problem?

Some say it's obvious: illegal and mostly Hispanic immigrants are taking jobs that could be held by native-born Americans. But it used to be obvious that housing prices could rise faster than wages indefinitely, so calling it obvious isn't good enough.

I spent some time this week reading survey research from the Pew Hispanic Center, a group of researchers in DC who study issues involving our nation's Hispanic population. They do a lot with vanilla Census data, but in late 2004 and 2005, they also managed to survey about 4,600 Mexicans, most of whom were undocumented immigrants, and those results are fascinating.

I read one Pew report pointing out that the employment prospects of native-born workers are not very well correlated with growth in immigration. Cities and states with lots of immigrant growth seem also to be places where it's not hard to find a job. This is, as is much social science research, not much of a surprise, on second thought.

The story of a couple other reports is more telling: our nation's job market has split into a collection of jobs held largely by Hispanics, many of whom are immigrants, and a collection held by everyone else. The first collection, including dishwashers, janitors, and landscapers, are low status and paid terribly, and the second collection largely isn't. Immigration probably has very little effect on this second collection, but in the first group, undocumented workers probably are holding down wages.

So what about just sending them all away? Ignoring for a moment, the monumental task of collecting and deporting 12 million people, if you could wave a magic wand and send all the undocumented workers home, you wouldn't magically get jobs for the people left behind. Why? Because these jobs pay too little for many people to survive on them. The Pew survey found that the median wage for immigrants was $300 per week. Another way to say it is that at least a third of the group surveyed were working for less than minimum wage, and that's only if you assume they're all limiting their work to 40 hours in a week. How do immigrants afford it if other people can't? By living with family, friends and boarders, and by paying more of their income for less housing than anyone else, according to a 2006 Notre Dame study I found. One in five Hispanic households headed by non-citizens have three or more wage earners in them. For the rest of us, it's about one in nine.

In other words, what would happen if all Rhode Island's undocumented immigrants could be transported elsewhere is that the job ads to replace them would go unanswered, except to companies who chose to pay higher wages, who would go broke because they'd lose all their business. (If you could make them all vanish at the same time, it might work, but we can't do that.)

Any business that employs immigrant labor, be it a janitor service company, a restaurant, a landscaper or a plastic molder incorporates the wages they pay into the prices they charge. Decades of dumb immigration policies have made it so that layers and layers of business now depend on these prices being very low. A software business may not rely directly on immigration, but they do rely on low rents, which in turn depend on bargain rates for janitorial services and landscaping.

And that's the real problem with immigration enforcement. We can make rules about not hiring undocumented workers (and we certainly have lots of those) but the sad truth is that our nation has hundreds of thousands of businesses whose business plan requires them to seek the cheapest possible labor. It's not as if this is a surprise, either -- this is part of the big-fish-eat-little-fish ocean of competition that businesses swim in. There's no point in feeling sorry for them, but we need to understand the fix they're in before useful policy solutions can be found. Simply telling them to become our enforcers by using E-verify (a tool that doesn't work) isn't going to do the trick because the honest ones will fail, and the cheaters survive.

Does this mean we're all doomed and there's nothing we can do? Not at all. Government has a plenty of tools at its disposal, but it has to use them on the right problem. In this case, the problem isn't just immigration, but the structure of the job market, that entire categories of jobs simply don't pay enough. We can help both by using the government's tools to begin to push up the wages of people at the bottom of the ladder, as well as to make life livable by people who subside there. We can raise the minimum wage or create and enforce living wage rules, or support union organizing efforts. We can also help people survive better on a lower wage by figuring out how to get health care out of employment decisions, improving the child care options for poor families, and pushing the market to provide more affordable housing.

Sadly, none of this is as easy to describe as simply demanding the impossible, preferably in tones of outrage. So our policy makers resort to that, time and time again, and everyone wonders why things don't get better.

21:02 - 10 Jan 2009 [/y9/cols]

Sun, 04 Jan 2009

Census Numbers: What Do They Mean?

Right before Christmas, the Census Bureau published its estimates for state population changes as of July 2008. The news wasn't great for Rhode Island, which is along with Michigan, one of only two states to lose population between 2007 and 2008. You can bet that this will provoke the usual round of teeth-gnashing, I am sure, and since most of the usual teeth-gnashers find everything to be a reason to cut taxes on rich people, you can bet that's coming, too.

But what is the story behind these numbers? Is it worth inquiring further about what they really mean? Your answer to this question will depends on whether you really want to solve problems, or whether you just enjoy complaining about stuff. I am interested in solutions, so I peeked, and this is some of what I found.

The first thing worth noting is that our population decline is less than it was last year. We lost a lot of people in 2005, but things have been getting better since then. This is the opposite of the case in Michigan, whose population loss is getting worse. By itself this isn't necessarily cause for comfort, but it does mean that whatever is going on here is probably not the same thing as is going on in Michigan. Undoubtedly a part of the problem is the lack of jobs here, but the population drop was greater last year, when the unemployment rate was much lower, so that's not really a satisfying explanation.

So, it seemed worth turning over some rocks. I looked some at the components of the changes: births, deaths, migration. One interesting thing is that our "natural" growth rate (i.e. not counting migration) is lower than many other places. For example, in 2007 we had 12 births per thousand people and so did the metropolitan Boston area. (The detailed numbers for 2008 aren't available yet.) But they only had 7.8 deaths per thousand people, while we had 9.3. Ours is an older population than in many other states.

Isn't this just an unimportant detail? No. Look at Connecticut's Fairfield County, which contains Bridgeport, one of the poorest places in New England, but also Westport, one of the richest in the country. Fairfield has only about 12% fewer people than our whole state. For every thousand people in Fairfield in 2007, 10.5 left for another place in the US, while 9.5 left here. But Fairfield's death rate is much lower, and they get more immigration from other countries, so they're holding steady in overall population.

At this point, I thought to myself, these numbers are only estimates. The Census statisticians are good at their jobs, and I'm not going to contradict them, but we have some real numbers, too. I recently saw a table of Rhode Island district school enrollments over the past five years, and those numbers are even more unsettling. With the exception of Barrington, all of our school districts have lost students since 2004. Some districts have lost more than 10% of their students over that time. South Kingstown and Providence have lost 12% and Newport has lost 21%.

Declining school populations reveal that the Census estimates are probably right, and since we seem to be losing a higher percentage of students, it's likely that the departing population is a lot of families with children.

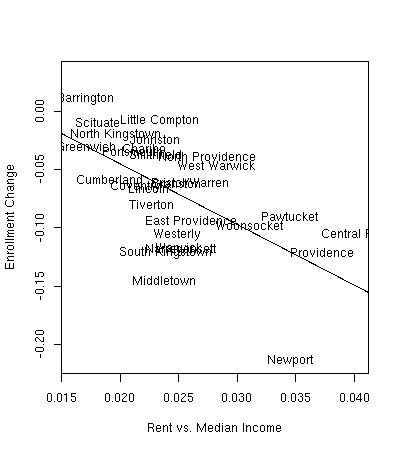

School enrollment data, because it's sorted by town, give us a way to probe for possible causes. I tried correlating the losses with other kinds of survey data about our towns, and wasted an afternoon testing variables like median incomes, per capita incomes, proportion of renters to owners and so on. The best correlation I found was with the ratio of average rents to income. The higher the average rent as a proportion of the average income, the more likely a district is to see enrollment losses. (You can find some of the statistical details and a pretty picture at whatcheer.net.) In other words, the more expensive the housing in a town, the more likely those schools are to have fewer kids today than in 2004. Our population loss is as likely to be an affordable housing issue as it is anything else.

None of this is to say these numbers are not very worrisome. Declining populations have real consequences for government services, and the most important consequence is that the cost of the services we provide goes down slower than the number of people they're provided for. It's sort of a reverse effect to economies of scale. It costs just as much to educate 20 kids as it does to educate 25, because you still need a teacher and a building and heat for the classroom and so on. Losing five kids does not mean you can cut five kids' worth of education funding, even if the state and lots of town councils try to manage things that way.

So what do we do about this? Right at the moment, of course, we can't really build much housing because of the fiscal handcuffs our leaders have put on. But building our way out of the affordable housing problem has never been a good option. We can address the housing market in a useful way -- with laws about housing speculation, and rules to preserve rental units and favoring rental income over capital gains. Addressing the real pressures on municipal budgets would help, too, since property taxes are a big part of rents. We must acknowledge that affordable housing is an economic development issue. You want jobs here? We need places for people to live where you don't have to go broke just to pay the rent.

13:27 - 04 Jan 2009 [/y9/cols]

The X axis is the ratio of median rents to median incomes, and the Y axis is the change in public school enrollment between 2004 and 2008. The line is fitted to the points using a simple least-squares method. For them who are interested, the slope of the line is good to about the 99% significance, while the intercept is only good to the 95% level. (See below.)

Update: The graph was mislabeled, leading to the impression that these numbers were much smaller than they are. I fixed the offending axis label, my apologies to all.

13:27 - 04 Jan 2009 [/y9/ja]