What's this? A Book!

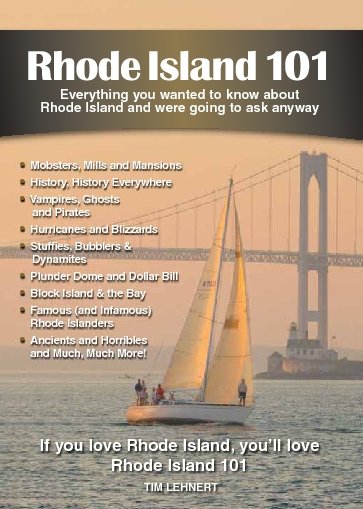

Or buy here: Light Publications, Powell's, or Bn, Amazon A look at the lousy situation Rhode Island is in, how we got here, and how we might be able to get out. Featuring

Now at bookstores near you, or buy it with the button above ($14, or $18 with shipping and sales tax). Contact information below if you'd like to schedule a book-related event, like a possibly entertaining talk on the book's subjects, featuring the famous mystery graph. Join the RIPR Mailing List! For a weekly column and (a few) other items of interest, click here or send an email to ripr-list-subscribe@whatcheer.net. RIPR is a (paper) newsletter and a weekly column appearing in ten of Rhode Island's finer newspapers. The goal is to look at local, state and federal policy issues that affect life here in the Ocean State, concentrating on action, not intentions or talk. If you'd like to help, please contribute an item, suggest an issue topic, or buy a subscription. If you can, buy two or three (subscribe here). Search this siteAvailable Back Issues:

Subscription information:

Contact:For those of you who can read english and understand it, the following is an email address you are welcome to use. If you are a web bot, we hope you can't understand it, and that's the point of writing it this way. editor at whatcheer dot net Archive:

AboutThe Rhode Island Policy Reporter is an independent news source that specializes in the technical issues of public policy that matter so much to all our lives, but that also tend not to be reported very well or even at all. The publication is owned and operated by Tom Sgouros, who has written all the text you'll find on this site, except for the articles with actual bylines. Responsibility: |

Fri, 30 Oct 2009

How many towns is the right number?

After years of talk, it seems like initiatives to consolidate municipal services and schools are actually moving, slowly, but perceptibly. The legislature has convened a commission to talk about it, which is interesting, though the kind of thing that only occasionally presages real action.

On the other hand, Senator Frank Ciccone, vice-chair of the Government Oversight committee, says he's going to introduce quite a dramatic bill in January, revoking all the city and town home rule charters in the state and creating five county-wide municipal and school administrations. I'm glad he's doing this, not so much because I agree with him that such a dramatic change is a good idea, but because change will only happen when someone proposes it. His efforts are far more likely to make a positive difference in your life than the commission's.

There are two reasons widely cited for consolidation. Actually, that's not quite true. There's one widely cited, but pretty questionable reason, and another seldom cited, but likely very important reason. They lead to very different conclusions about what needs doing, and I don't expect the commission to reach those conclusions.

The widely cited reason is just the desire to achieve economies of scale. Thirty-nine cities and towns means thirty-eight police chiefs (Exeter doesn't have one), thirty-nine public works chiefs, thirty-six superintendents of schools and so on. Proponents of consolidating services long for a situation where there's just one, and slaver over the possible savings.

But what kinds of savings are actually possible? Look at schools, for example. Around the state, the average overhead of school systems is about 6% of revenue. That means that about 6 cents of every dollar goes to administration. But in larger school systems, like Fairfax County, VA, the overhead is also around 6%. Why should we imagine we can do so much better?

Sure, if all of the state was one school district, we could do away with 35 superintendents, but you can bet we'd need a bunch of new deputy superintendents. You only achieve economies of scale when there is excess capacity, and if it can't be used in the current configuration. Where there's slack, there may be savings. But do you know that there's slack in your town's management, or do you only think that because you hear it on the radio? I'm not saying there is or isn't in your town, but I am saying it's worth being skeptical.

In other words, the savings found by combining public works departments are pretty speculative. There will doubtless be some, but will it be enough to be worth the fighting? Maybe.

However, there's that other reason you don't hear as much about. When a family moves from Cranston to Exeter, Cranston loses a little of its tax money, and Exeter sees an increase in the demand for its services. For most services, Cranston can't cut expenses as fast as they lose dollars. This isn't because of unions, but simply because of arithmetic. A hundred fourth-graders in a school make four classrooms. But ninety-nine students also make four classrooms. Just because you've cut the students doesn't mean you can cut the payroll, and the same effect is apparent with police, fire protection, sewers and more.

On the flip side, many studies have shown that the new residents of a town like Exeter seldom pay enough in taxes to cover the services they demand. This is especially true since most services cost more to provide way out in the burbs, where people are far apart from each other. It's why towns invented developer impact fees.

But what this means is that when people move from one town to another, the town they move from feels pressure on their tax collections and the town they move to feels pressure on their services. The result is that taxes can go up in both towns.

What's more, in the town that's growing, the demand for new tax dollars can be partially met by new residents the next year. New residents and inflation mean the town's costs are going up 3%, but that's OK because the town council thinks there will be 3% more new residents the year after, too. Growth allows towns to artificially hold down their taxes -- until the growth stops.

The paradox of Rhode Island town finance is that today, the places with low taxes are the suburbs where the services are most expensive to provide, while the places with the highest taxes are the cities, where services are cheapest. It's the movement of people, and what it does to the tax rolls in towns, that bring us to this peculiar, and probably not stable, spot.

Another way to look at this is that the only way consolidation of town services will actually reduce pressure on taxes is if the taxing and planning functions are also part of the consolidation plan. Not until town finances can be partially insulated from the effects of people moving a short distance will we see these kinds of pressures relieved. Unfortunately, this is not likely to be on the commission's agenda. They're more likely to be studying the obstacles to combining public works departments and school systems. This is useful, but it's just not going to save the dollars you might hope, and will cause a lot of yelling along the way.

So bravo for Senator Ciccone, who at least has the honesty to put forward an idea that will actually make a big difference. People who insist we should hold the line on municipal costs by consolidating services shouldn't discard it out of hand, but welcome his contribution, and look for the ways to make his idea better.

21:02 - 30 Oct 2009 [/y9/cols]

Coverage of the book... Brown Daily Herald.

13:21 - 30 Oct 2009 [/y9/oc]

Another take on binding arbitration

Read here

The rank and file rejection of the first contract proposal was a huge setback for school reform in Providence. It weakened the administration, helped trigger a decade long cycle of revolving door superintendencies, divided the union, and as the final contract included both a bigger pay raise and fewer concessions in work rules, reinforced the idea that intransigence by the union would be rewarded. Also, the entire conflict triggered a long period of "work to rule" right as a whole range of promising reform initiatives were ramping up.If Rhode Island had binding arbitration in 2000, everything would have been different. No work to rule, and the orderly adoption of a contract that would have probably closely resembled the original agreement between administration and union leadership. This would have been followed by two more contracts that progressed in an orderly way toward more reasonable work rules, and we'd be working on the fourth in that series right now.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, a look at recent history confirms that binding arbitration would be good for school reform in Rhode Island.

13:04 - 30 Oct 2009 [/y9/oc]

Fri, 23 Oct 2009

Why are people still losing their homes?

Reports out this month tell us that the foreclosure crisis facing our nation has not even peaked yet. Nationally, one property in every 136 were in some kind of foreclosure proceeding in July, August or September -- 937,840 properties. According to RealtyTrac, a private concern tracking them, foreclosures are up 5% from the spring quarter, and 23% from the same time last year.

The hardest hit places in the country are the places that have boomed the fastest over the past decade: Nevada leads the list with one foreclosed property for every 23. Arizona and California aren't far behind, with 53 in both.

To my great relief, our state appears to be bucking this trend, and foreclosures seem to be declining slightly in Rhode Island. We've seen the rate decline 6.3% since the spring, and about 2.75% since the same time last year. The rate here is still nothing to brag about: one foreclosure for every 290 properties, still high enough to be devastating to many neighborhoods.

In fact, the whole list is dismal, except way down on the bottom, one bright spot: Vermont. Last quarter, while Rhode Island was seeing 1,554 foreclosures, Vermont saw 62. This comes out to about one foreclosure for every 5,023 properties.

So how did they avoid this crisis? I read one news account that attributed it to innate Vermont thrift, and how that kept people from overextending themselves. We policy wonks have a technical term for that kind of analysis: dumb. We are blind if we ignore cultural differences between states, but we're also blind if we stop looking for reasons beyond a stereotype like this. Besides, New Hampshire yankees are every bit as legendarily thrifty. They're right next door, too, and they saw 1,944 foreclosures in the last quarter, 1 out of 306 properties.

So what's the story in Vermont? It seems to be a long one, but not too complicated. Their real estate market never flew as high as ours, and there are several reasons why. The permitting process for new construction is quite onerous in Vermont, even by Rhode Island standards -- did you know that you're generally not allowed to build at all on prime agricultural land there? Also, Vermont has an interesting tax on the capital gains from resale of land. If you keep real estate for more than five years, there's no tax, but if you flip it quickly, the tax is quite high. (It can be 90% of the gains if you're flipping very quickly.) This tends to keep speculators away and housing costs down. Vermont has had a crisis in affordable housing, but housing inflation there was half of ours between 2000 and 2006. In other words, we should envy their "crisis".

There's more. Vermont also has an interesting limit on mortgage fees and interest rates. It's a little complicated, but basically if a bank wants to charge you more than a certain amount of interest they have to give you a list of banks that charge less. They even require the list to be on a colored sheet of paper so it doesn't get lost in the piles of paper generated by mortgage closings.

One of the regulations I find most interesting is a modest couple of lines in regulation B-96-1 of the banking code. This declares that to do business, a broker must sign an agreement with the borrower that he or she "represents the interests" of that borrower. In other words, if a borrower goes bust, the broker can be involved if it seems the mortgage terms might have something to do with it.

Thomas Candon, the Deputy Banking Commissioner in Vermont, told me he thought this was an important part of keeping lenders in check, along with language in the banking legislation preamble prohibiting "unconscionable lending practices." According to him, both of these have been to court a few times, and both have resulted in the termination of several abusive lending practices in Vermont. It's harder to get a mortgage in Vermont, but as we've seen, this isn't all bad.

The result of all this is lots of complaints by Vermont banks and real estate agents, who point to the millions earned by their peers in other states and wish they could pull in the big bucks like that. But the other result is that as of now, Vermont really doesn't have a foreclosure crisis at all. Their economy didn't fly high, but over the past decade, it has grown faster than in New Hampshire, Massachusetts or Connecticut, even if those others outpaced them in one year or another. Slow and steady isn't just one of Aesop's morals.

Despite the gravity of the foreclosure crisis, it's remarkable to me that even now, a year and a half after it set in, there has been essentially zero helpful response from Congress or the state. Hamstrung by "conservatives" whose fealty to free market principles demands they stand by as unconscionable lending practices brought our economy to its knees, simple proposals such as changes in bankruptcy laws or allowing judges to change mortgage terms ("cramdown") have failed.

In the department of better late than never, Congress is right now debating the creation of a consumer protection agency for finance. A bill to establish such an agency is being marked up in its House committee this week. After that, it goes to the Senate Banking Committee, where Senator Jack Reed is the second banana. If you agree with me that abusive lending practices played a huge part in precipitating the financial crisis, it would be worth telling him so, before the bill is heard there.

21:55 - 23 Oct 2009 [/y9/cols]

Fri, 16 Oct 2009

This coming Friday, October 23, I will give a talk and sign some books at Westerly's Other Tiger bookstore, 90 High Street, Westerly, from 5-7pm. Please come, and more important, tell anyone you know in Westerly. I don't know enough people there, so any help is welcome.

Also, I was on Channel 36's Lively Experiment last night. They re-broadcast it on Sunday at noon, so look for it this Sunday.

18:55 - 16 Oct 2009 [/y9/oc]

I saw Michael Moore's new movie, Capitalism, A Love Story, a week ago. The movie was a little messy, but -- like his other movies -- is filled with interesting stories about our country that you never see on the news. For example, there were the companies run as cooperatives, like an industrial bakery in California and a robotics factory in Wisconsin. In those companies, decisions are made collectively, and both are profitable, despite decent pay for the workers, and relatively modest pay for the executives. There was the sheriff of Cook County, Illinois, announcing that he would no longer evict people because of foreclosure just on the say-so of the banks. (He said he would still evict people for whom the bank actually had the paperwork.)

It's a good movie, partly because it's funny and partly because it's really not that funny. There's a lot of human tragedy portrayed in it, which isn't too surprising, since that kind of thing is pretty much everywhere you look. For example, there's plenty of tragedy to be found in the boarded-up houses in South Providence, not very far from the homeless shelters bursting at the seams. There's tragedy in the way our manufacturing heritage has been systematically dismantled by the very people in charge of it. High wages so often get the blame, but the behavior of the executives who closed profitable factories in order to open more profitable factories elsewhere is routinely disappeared.

America today is a land of contrasts like this, brought to us by free enterprise, and our collective unwillingness to moderate it. Free enterprise is an amazing and efficient way to organize an economy to produce things we all need, but there are good things -- affordable housing, clean air and water, public transit -- it just does not or cannot provide. Of course, it does provides the opportunity for an individual to amass unimaginable wealth, at least in theory, presumably why lots of us put up with the contradictions.

One big problem with free markets is that there are a lot of clever people out there looking to make money in them, and these clever people can do wonderful things for all of use, but they can also distort some useful things, too, which isn't so helpful. The "market" drives them in both directions. For example, Moore's movie makes much of "dead peasant" insurance policies, where a company buys life insurance on its employees, not for its employees. This is a distasteful practice, to be sure, but it's also a perversion of the whole concept of insurance.

Insurance was invented as a way to share risk. I have a health insurance policy, but I'm not using it much right now (knock on wood). This means that I'm essentially paying someone else's medical bills with my premium dollars. I do this in the hope that when I or someone in my family gets sick, someone else will pay our bills. (This is what makes it so laughable to see signs at health reform protests about not wanting to pay for other people's bills. Most of those people -- the healthy ones who have insurance -- already are paying other people's bills when they pay their health insurance bills.)

So that's the point behind insurance: sharing risk. The idea is crucial to protecting the finances of many people's lives. But what the companies do when they take out dead peasants policies is nothing more than gambling. They are betting that the health data available to them from their employee health plan are better data than an insurance company has.

Well fine. I buy a lottery ticket from time to time; what's the problem with gambling? Just this: they're betting in the same market that other people use for things they actually need. The bets on those life insurance policies affect the rates charged to everyone else, and if the companies are winning those bets (and the practice wouldn't have spread unless it was easy to beat those odds) the rest of us pay higher premiums.

You see the same issue in other markets. Housing gamblers ran up the prices in the poorest neighborhoods of our state, leaving prices far out of the reach of the poor people who live there. Currency gamblers have a tremendous effect on the money we use to buy stuff. The leveraged buyout artists who engineered all those corporate takeovers over the past 30 years gambled with the future of their companies, risking their employees' jobs on something beside the price and quality of the products they made. And, of course, the banks and hedge funds who are credit market gamblers were betting with bank credit. When that market broke last year, many businesses who actually needed credit lines to expand or just to stay afloat sank instead.

The point is that housing, risk sharing, jobs, bank credit and money are important to all of us. Risk is an unavoidable part of our system, but reckless risk isn't. When we allow people to gamble recklessly with these things, we make life much harder for the rest of us whose comfort, careers, and even lives depend on them. Gambling can be a good time, but none of us should be forced into a casino against our will.

And of course there's one more thing: in 21st century America, you can be vilified simply for bringing obvious stuff like this to other people's attention. That, of course, is Michael Moore's great crime. But this is no way to run a country -- or a state. Fixing problems demands honesty in their evaluation. This is important not because it might be a triumph for my favorite ideology or yours, but because if you don't get the diagnosis right, your solution won't work, and the problems won't go away.

18:03 - 16 Oct 2009 [/y9/cols]

Fri, 09 Oct 2009

When the legislature comes back into session later this month, rumor has it they may pass a law saying that when teachers and school committees can't come to an agreement through negotiation, they can submit their dispute to arbitrators for settlement. The arbitrator's decision would be legally binding on both the committee and the union, so it's called binding arbitration.

This would be a welcome development to many. Right now, when there is no agreement in a labor dispute like these, things enter a kind of legal limbo, where there are essentially no rules. Thus you have the East Providence school committee declaring that if they simply refuse to negotiate, they can let a contract expire and then ignore it entirely. On the other side of the coin you have the impasse with the Providence firefighters, whose contract terms remain in force until a new contract is signed, according to a clause in their old Cianci-era contract. They therefore have an incentive to stonewall negotiations. (I'm not saying they've done that -- I don't know -- but I am saying the deadlock isn't entirely to their disadvantage.) Neither outcome seems particularly beneficial to me.

The fact of the matter is that municipal employee unions exist. We can't wish them away, and we shouldn't try to legislate them away, either.

Why not? There are decent economic reasons having to do with prevailing pay and keeping a floor on wages in the local economy. But at least as good a reason is that one of the important lessons of history is that in most wars, both sides lose.

To me, the binding arbitration process seems as good a way as any to resolve these kinds of conflicts. In binding arbitration, two sides present their "last best" proposals to a neutral panel of three arbitrators (one chosen by each side and one chosen by both) who decide between them. The arbitration statute spells out the permissible grounds for a decision, too, so it's not as if arbitrators can just make stuff up.

What's more, we have some useful experience right next door, in Connecticut, where binding arbitration has been the law for teachers for 30 years.

But wait, Connecticut has binding arbitration; Connecticut also has about the highest-paid teachers in the country. Are these facts related?

Well, no. The binding arbitration law in Connecticut was created in 1979, in response to a dramatic teachers' strike in Bridgeport the previous fall. The teacher union went out on strike, but a judge ordered them back to work and when they didn't go, had them all arrested. According to differing accounts, somewhere between 265 and 274 teachers were arrested and held for two weeks in an old WWII POW camp in Windsor Locks.

The strike happened because Bridgeport teachers couldn't come to an agreement with the administration, and there wasn't any other way to force the issue. And that's really the point behind binding arbitration: to force two sides to negotiate. The real hope is that no contracts have to be arbitrated, and that both sides will see arbitration as a risk they don't want to take.

But still, could binding arbitration be why Connecticut teachers are among the best-paid in the country? Not likely.

In 1986, despite seven years of binding arbitration law, Connecticut teachers were only 19th in the country in surveys of teacher pay. The average teacher salary then was around $13,000, and it was not hard to find teachers moonlighting as weekend bartenders, editors, writers, and construction workers, where they were paid more than their "main" gig.

As a result, teacher recruitment was challenging, especially in Connecticut's urban districts. Which is why 1986 saw Governor William O'Neill get behind passage of a law specifically designed to push up teacher salaries. The "Education Enhancement Act" that year increased teacher qualification requirements, but it also set a minimum salary for teachers of around $20,000, and provided $300 million in new state funds to Connecticut's 160-odd school districts to pay for these increased salaries.

In other words, it was the stated policy of that state's Governor and Legislature that teacher salaries needed to go up, by a lot. Tom Murphy, the spokesguy for the Connecticut Department of Education put it to me this way, "We're first or second in the nation now, and that's a good thing if you're interested in recruiting good candidates." He boasted to me that they now get lots of good candidates moving in from Rhode Island. (I know a couple, too.)

In other words, the imposition of binding arbitration didn't push up teacher salaries in Connecticut, the former Governor did, and he did it on purpose.

Does arbitration in Connecticut favor teachers? There, too, the evidence doesn't really say so. In 2004, one of the Connecticut teacher unions (the CT Education Association) put out a report on the subject. By their count, between 1994 and 2003, 75 contracts went to arbitration (out of 638). In judging those contracts, arbitrators chose the school board's side on 379 of the 756 issues, and 377 times in favor of the teacher unions.

According to their deputy director, Patrice McCarthy, The Connecticut Association of Boards of Education's position is that they think binding arbitration is fine and shouldn't be repealed, but they wish the grounds on which the arbitrators decided things were a bit more expansive, with more of an emphasis on the financial health of the town doing the negotiating. These might be workable ideas, but remember that the whole point is that arbitration be a distasteful alternative to both sides.

So that's the issue. In the papers and on the radio in the coming weeks, you'll hear that binding arbitration is actually the fifth horseman of the apocalypse, all foam and fangs and ghastly mien, come to ravage your children and your school budgets. Just remember, though, that in the state right next door, this same guy has been quietly planting daisies for the past 30 years, and there hasn't been a single teacher strike since he arrived.

23:37 - 09 Oct 2009 [/y9/cols]

It seems the FTC intends that all bloggers disclose the products and services they get for free.

Seeking guideline clarification, blogger Edward Champion interviewed FTC spokesman Richard Cleland on Monday. In Cleland's view, a blogger who kept a free book that he reviewed on his site would have to disclose this "compensation.""If there's an expectation that you're going to write a positive review," Cleland told Champion, "then there should be a disclosure."

This is an odd reading of how reviews work. That is, "expectation" is a funny word. "Hope", "chance", "prospect" all seem more apropos. Plus, I don't see newspapers running to mention this in their articles. Why might they be exempt?

But be that as it may, let this note serve as full disclosure to everyone who cares to know that some publishers are generous (perhaps some would say unwise) enough to provide me with free copies of their books to review.

12:07 - 09 Oct 2009 [/y9/oc]

Mon, 05 Oct 2009

The House By the Side of the Road

by Sam Walter Foss

Let me live in a house by the side of the road,

Where the race of men go by -

The men who are good and the men who are bad,

As good and as bad as I.

I would not sit in the scorner's seat,

Or hurl the cynic's ban;

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I see from my house by the side of the road,

By the side of the highway of life,

The men who press with the ardor of hope,

The men who are faint with the strife.

But I turn not away from their smiles nor their tears -

Both parts of an infinite plan;

Let me live in my house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I know there are brook-gladdened meadows ahead

And mountains of wearisome height;

And the road passes on through the long afternoon

And stretches away to the night.

But still I rejoice when the travelers rejoice,

And weep with the strangers that moan,

Nor live in my house by the side of the road

Like a man who dwells alone.

Let me live in my house by the side of the road

Where the race of men go by -

They are good, they are bad, they are weak, they are strong,

Wise, foolish - so am I.

Then why should I sit in the scorner's seat

Or hurl the cynic's ban?

Let me live in my house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

Foss was born in New Hampshire, but, a graduate of Brown, is interred in Providence's North Burial Ground.

14:15 - 05 Oct 2009 [/y9/oc]

Fri, 02 Oct 2009

As we teeter back and forth between layoffs and no layoffs of state employees, it gets hard to keep track. Last week, the AFSCME Council 94 local presidents who rejected the Governor's offer relented and agreed to put the Governor's offer before their memberships for a vote. To recap, this offer would have some unpaid work days this year and next, but would offer extra vacation days further down the line, or compensation days upon retirement, and it would put off a pay increase. The more controversial part of the proposal involves allowing managers to reassign employees to different state departments where the employees might be represented by a different union.

The AFSCME local members are voting on the proposal this week. While we wait to see how this turns out, I think it's worth looking at part of the "structural deficit" that plagues our budget.

The structural deficit is just the fancy term for the deficit next year (and the years after). It's an acknowledgement that revenues and expenses do not match, despite what we may have done or not done to patch it together for the current year.

Obviously, the structural deficit is due to the decline in tax revenue. I've written before that this decline was first self-inflicted, and then made worse by the tanking economy. But part of the structural deficit that gets no attention is even more important and that's the unwillingness of your leaders to say what, exactly, we are sacrificing. It's sort of a candor deficit.

It's fine, that is, to say we must do more with less, but it's little better than a comedy skit to claim we can do it year after year after year. At some point, grim reality interferes. And yet, you don't see anyone -- Governor or legislator -- saying "We're going to close the Department of Elderly Affairs," or "We're going to have a moratorium on bridge repairs," or "We're not going to be doing any enforcement at DEM this year." Instead what happens is that a little more maintenance slips by, a little more service is put off, the work backlogs grow a little bigger, the enforcement divisions lose another tooth.

And we take on more debt. Since 2002, state debt has more than doubled, if you count the 'off-books' GARVEE debt taken on by the Department of Transportation. As of fiscal year 2003, Lincoln Almond's last budget, state debt was around $1.25 billion. By the end of this fiscal year, it will be over $2.1 billion, plus another $550 million or so of GARVEE bonds, with another couple hundred million to come. These bonds were issued in order to build the fancy new bridge in Providence, and to replace the Sakonnet River bridge, and a couple of other big projects. In a purely technical sense, they are not general revenue debt (so needed no referendum) but in a practical sense, they are every bit the load on the state budget as any DEM open space bond.

For the managers and directors of state departments, most of whom don't belong to a union and who serve at the pleasure of their superiors, there is tremendous pressure to say, "Yeah, we can get it done," even in the face of perpetually declining budgets. But you can see the results in records of departments' performance, published each year in budget documents.

A number of the performance measures are silly choices, seemingly designed only to make the department look good. The Department of Transportation claims highway fatalities as a measure, for example, which are only tangentially related to any department activity. But some departments have chosen realistic measures of their capacity. And pretty much wherever they measure capacity, you can see it going down. For example, you'll see that the percentage of large air pollution sources getting their annual DEM inspection on time has declined from 57% in fiscal 2003 to 32% in fiscal 2008. (The numbers in this document after 2008 are only estimates, and optimistic ones at that.) The notes mention that this poor performance has caused the goal of 100% to be changed to 50%. No doubt you'll find that reassuring.

In addition, there are fewer neglect and abuse cases getting timely treatment from family court, fewer successful investigations in the fire marshal's office, higher caseloads in the public defender's office, and fewer municipal comp plans getting timely review. These numbers are from before the huge wave of retirements a year ago, so there's no reason to think they've improved. Anecdotally, I hear only stories of gloom and work backlogs from state employees I talk to.

The truth is that it is fundamentally dishonest to pretend that our government can sustain the losses of people and resources year after year without suffering the consequences. But why don't you ever hear about this? It's because in many cases, the programs hardest hit are popular, or exist to save money. Environmental protection, for example, enjoys broad popular support, even if people grumble about permitting. Transportation projects, too, are popular, and maintenance is about saving money, as are such controversial programs as Medicaid for the poor. What's not popular is paying for all this, but I thought that's what the "tough" decisions we're always hearing about are supposed to be for.

Last week, testing results showed that science education in the state seems to be falling behind. Test scores showed our children not performing particularly well on the NECAP science assessment tests, either compared with the other states that administer this test or with our own record of previous years. The Governor termed the results, "unacceptable," and promised action of some sort. That's great, but when the dust settles, who will be left to act?

18:09 - 02 Oct 2009 [/y9/cols]