What's this? A Book!

Or buy here: Light Publications, Powell's, or Bn, Amazon A look at the lousy situation Rhode Island is in, how we got here, and how we might be able to get out. Featuring

Now at bookstores near you, or buy it with the button above ($14, or $18 with shipping and sales tax). Contact information below if you'd like to schedule a book-related event, like a possibly entertaining talk on the book's subjects, featuring the famous mystery graph. Join the RIPR Mailing List! For a weekly column and (a few) other items of interest, click here or send an email to ripr-list-subscribe@whatcheer.net. RIPR is a (paper) newsletter and a weekly column appearing in ten of Rhode Island's finer newspapers. The goal is to look at local, state and federal policy issues that affect life here in the Ocean State, concentrating on action, not intentions or talk. If you'd like to help, please contribute an item, suggest an issue topic, or buy a subscription. If you can, buy two or three (subscribe here). Search this siteAvailable Back Issues:

Subscription information:

Contact:For those of you who can read english and understand it, the following is an email address you are welcome to use. If you are a web bot, we hope you can't understand it, and that's the point of writing it this way. editor at whatcheer dot net Archive:

AboutThe Rhode Island Policy Reporter is an independent news source that specializes in the technical issues of public policy that matter so much to all our lives, but that also tend not to be reported very well or even at all. The publication is owned and operated by Tom Sgouros, who has written all the text you'll find on this site, except for the articles with actual bylines. Responsibility: |

Fri, 31 Oct 2008

Here's a funny endorsement:

As anyone in academia will know, a thoughtful and professorial air is not in itself a recommendation for executive power. But a commitment to seeking good advice and taking seriously the findings of disinterested enquiry seems an attractive attribute for a chief executive. It certainly matters more than any specific pledge to fund some particular agency or initiative at a certain level — pledges of a sort now largely rendered moot by the unpredictable flux of the economy.This journal does not have a vote, and does not claim any particular standing from which to instruct those who do. But if it did, it would cast its vote for Barack Obama.

Well, not that funny an endorsement, but a funny source: Nature, one of the two most prestigious journals of science in the world.

10:20 - 31 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]

Tue, 28 Oct 2008

Heartwarming examples of civic engagement...

... or rancid acts by democracy-hating extremists. You decide.

07:23 - 28 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]

Fri, 24 Oct 2008

Is out after an inexcusable delay, my apologies.

- What is the real source of the financial crisis? It's not mortgages, and it's not derivatives either, really. Too much capital?

- Graph of the month! Profits v. wages, Republicans v. Democrats.

- Word games with Medicaid, by David Rochefort and Kevin Donnelly. Does how it's said affect what you hear?

22:42 - 24 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]

Wed, 22 Oct 2008

RIPR Award for absurd campaign literature

These are the candidates (with working web sites) mentioned in this week's column:

- Christine Spaziano, Republican candidate for Senate District 4 (Providence)

- Larry Signore, Democratic candidate for Senate District 32 (Barrington/Bristol)

- Tim Lee, Republican candidate for House district 21 (Warwick)

- Steven Hart, Republican candidate for House district 28 (Coventry)

- Chris Ottiano, Republican candidate for Senate district 11 (Portsmouth)

- Robert Paquin, Republican candidate for House district 19 (Warwick and Cranston)

- Dan Reilly, Republican candidate for House district 72 (Portsmouth and Middletown)

- John Pagliarini, Republican candidate for Senate district 35

- Bill Connelly, Republican candidate for Senate district 36 (North Kingstown/Narragansett)

10:57 - 22 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]

Tue, 21 Oct 2008

Maya McGuineas, of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, on the possible stimulus bill the next Congress might pass: "I just hope they don't pork it all up... just so it's not spend spend spend"

I used to aspire to do satire, but why bother?

20:59 - 21 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]

Sat, 18 Oct 2008

So there are exciting times on Wall Street. But what does the financial crisis mean for those of us who aren't borrowing or lending? Well, the credit markets serve not just businesses but governments, too.

Our state and local governments issue bonds not just for building things, but also for cash management. That is, sometimes the tax revenue doesn't come in synch with the bills to be paid. In those cases, cities and towns can issue "tax anticipation notes", short term loans to help cover the bills until the tax collections pick up. It's a pretty typical cash management technique. Borrowing for a few months at 3% isn't a huge cost, and if it means not having to build up a big cash reserve, so much the better.

But this only works so long as the credit market works and the rates are low. East Providence has used anticipation notes fairly routinely in the past, and was intending to do so this fall. Last year they borrowed about $25 million at 3% interest sometime in December, and paid it back when property tax collections started arriving in the summer. They anticipate about the same need this year, but at the moment, interest rates are running at more than triple what they've paid in the past, not to mention some uncertainty their bonds would sell at all. Right now, their policy is to hope this all clears up by December since they only have around $4 million in reserve. If it doesn't, there's big trouble.

The state frequently uses anticipation bonds, too. But they skipped a prospective issue this month, and borrowed from the TDI fund instead. This isn't such a bad idea, really, since the fund itself is going to have some trouble finding decent investments in the near future. The state will pay interest at a rate comparable to what the fund would be able to get.

But though the state has resources it can use to insulate itself, it it's hardly immune to the credit market freeze-up. A scheduled bond sale by the Clean Water Finance Agency will be put off until next year. This agency provides funds for cities and towns to make improvements to their waste-water and drinking-water systems. Among others, North Kingstown is planning to deal with lead contamination issues at two of its wells, and Newport has some dam repair projects as well as improvements to its storm-water sewer system pending. All told, around a half-dozen cities and towns have around $45 million in projects about to begin that depend on funds from the CWFA.

CWFA has cash reserves from previous projects, so is able to provide bridge loans to the cities and towns it serves until the bonds can be sold. In a related move, North Kingstown has signed contracts for constructing a new senior center, so they're moving ahead using funds from their budget reserve, even though the $4 million bond sale to cover the costs will be put off. If the markets recover soon, moves like these will seem smart. However...

The open market is one of history's most impressive achievements in allocating resources. Among a zillion other cool feats, the market for money itself has created a way to streamline governments by allowing them to tap a vast pool of investment funds to help manage their cash flows and invest in infrastructure projects.

But this is true only so long as the markets function well, and cheaply. We now know that this isn't a law of nature. None of us know how this turmoil will settle out, but it's fairly likely that government borrowing for routine infrastructure projects is going to be harder and more expensive than it has been. Even once sense is restored to the market for state and local government bonds, the pool of money from which they'll draw and the number of willing lenders is going to be smaller.

Here's another safe bet: With a number of commercial banks near failure and with a dwindling number of safe places to keep one's money, it's going to be a long time before the interest on bank accounts is anything more than nominal.

A state-run infrastructure bond bank might be a way to solve both those problems. Done right, this would be a way for any citizen to use a savings account to invest in improvements in their own community. In return, they'd have a safe place to keep their money, at decent rates (tax-free, too). Right now, our national markets price bonds from anywhere absurdly low because faraway bankers have no idea of their value. But the market isn't always right; people who live in a town or a state not only have a sense of its value, but also a stake in it.

Proposals like this have been met in the past with imputations of socialism. I heard this with my own ears, for example, one winter day in 1991 when I was wandering around the statehouse trying to interest General Assembly members (and anyone else who would listen, frankly) in a proposal I'd written up for a state-run infrastructure bank as a solution to the credit union crisis. But -- thank you Henry Paulson! -- now that you and I are part owners of a huge insurance company and soon some banks, too, I have a much more effective comeback to this kind of inane critique than I did back then.

Over the next few years, after we're done reeling from this financial shock, we're going to need all the good ideas we can find in order to get back up again. Idolatry of the free market has got us into this mess. Let it not complicate the business of getting us out, too.

00:47 - 18 Oct 2008 [/y8/cols]

Fri, 10 Oct 2008

Sometime during the Ford administration, legend has it that Wall Street Journal editor Jude Wanniski and two White House officials named Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney sat down for lunch with the economist Arthur Laffer. During the meal, Wanniski said Laffer drew the famous "Laffer Curve" on his napkin, and our government has never been the same since.

The Laffer Curve? That's a graph that shows that if you raise taxes too high, tax revenue drops. Conversely, if you're above some magic point on the graph, lowering the tax rate will increase revenue.

But the whole thing is essentially a fairy tale, beginning with the napkin. As Laffer himself told it, the restaurant had cloth napkins and "my mother had raised me not to desecrate nice things."

But what about the economics? In a certain sense, of course, the Laffer Curve is valid, even obvious. In an abstract world, it is indeed possible to imagine a tax high enough that raising it further would lower revenue. However, stepping back into the real world, few real governments could actually impose such a tax. Ours never has, and despite legions of economists looking for examples, no one has ever demonstrated that this effect is observed in the world in which you and I live.

You'll hear people who've drunk the supply side Kool-Aid say that the Kennedy tax cuts or the Reagan cuts or even the Harding-Coolidge cuts were good examples, because tax collections increased after they were enacted. But all of these cuts were accompanied by massive increases in government spending or the end of a recession or the end of punitively high interest rates or some combination of the above that turned out to be much more important effects. The toothlessness of Nixon's 1971 tax cuts never seems to come up.

However, imagine that it were possible to prove that some tax cuts have actually increased revenue. Even so, Laffer himself never suggested that tax cuts *always* raise revenue. And yet, reviewing some literature and web sites for candidates to the General Assembly this past week, it seems that a number of them believe exactly that. Of course, this is the dominant point of view at the state house, where the only economic plan offered in the past several years is for yet more tax cuts. So if elected, they'll feel right at home.

I sent a note to Steven Hart, a Republican running for state Representative in District 28 (Coventry), who wrote on his web site that "crippling tax increases" had damaged our economy. Since the last increase in a broad-based state tax was 15 years ago, I wrote to ask what he meant. He wrote back that "Lowering the [corporate income tax] rate would attract businesses to locate here which will provide additional tax revenue and create jobs..." Well, perhaps.

Much more straightforward was the approach of James Haldeman, another Republican running in Wakefield (District 35). He wouldn't tell me what he'd cut from the budget in order to cut tax rates: "My emphasis is on reducing tax rates! If we lower tax RATES significantly (on business and the individual) we will actually generate more tax RECEIPTS." [his emphasis]

Let's go to the numbers. The corporate tax is 9% of income and is paid by about 2,500 corporations. Not counting the companies who pay the $500 minimum (44,000 of them!), this tax raised $134 million in 2007. Were we to trim it to 8%, we'd need to raise $14 million in new revenues to make the cut pay for itself. Counting income and corporate taxes, that's the equivalent of 130 new companies with income of around half a million each, and with an average payroll of more than $2 million. Do you think this is a likely outcome of a small cut in one tax?

What about the income tax? Rhode Islanders earn around $40 billion a year these days. Out of that, we pay about $1 billion in income tax each year. In order for a 5% cut in the income tax to pay for itself, it would have to cause a 5% rise in personal income, roughly equivalent to the growth rate in 2003 and 2004. But ask yourself: what effect would a 5% cut in your state income tax have on you?

If you're part of a family earning around $75,000, a 5% cut in your income tax will be worth around $100. That's going to net a lot of economic stimulus, isn't it? Maybe you expect more rich people to move in, or put your hopes on the merchants and tradespeople they pay to re-spend the money they receive (the "multiplier")? Well, if we were actually an island, if nobody put their tax cut in the bank, if everyone spent it all as fast as they could on local businesses *and* if five hundred really rich people moved in because of the cut, then there'd be a fighting chance of making it pay for itself. Maybe. A larger cut would require a larger effect. Applied to the real world of Rhode Island's taxes, the whole proposition is completely absurd, but it so often comes masked in economic gobbledy-gook that people are routinely taken in.

Here's the bottom line: lower state taxes means less state revenue. You may think that's just fine, or you may not. Either way, don't trust candidates like Hart or Haldeman who promise the utterly impossible. Make them say what they'd chop for their tax cuts. Faith in the impossible has brought our state to a position where we have the wherwithal to do just about nothing in the face of the economic crisis facing us. Our fiscal crisis is going to get worse before it gets better and believing nonsense is not going to help one bit.

23:03 - 10 Oct 2008 [/y8/cols]

Mon, 06 Oct 2008

Well, not so big, but the big picture when you consider that each of us has choices to make in our lives, and are forced to live with the consequences. In dealing with the personal (and mental) consequences of staring into the uncertain future, Judith Warner nails it, for some of us.

09:23 - 06 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]

Sat, 04 Oct 2008

A Failure to Plan for Failures

As the nation continues to reel from the ongoing financial crisis, the boom and bust that we're suffering, it's worth stopping to ask how it is that we got to this place.

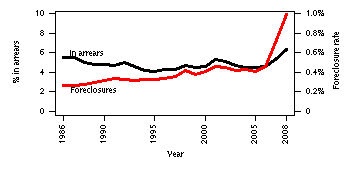

Everyone knows that foreclosures are driving the economic crisis, but does everyone know that people falling behind in their payments isn't the big story? According to HUD statistics, in 1986, about 5.5% of all mortgages were in arrears, and about one in 21 of those went into foreclosure. In the first quarter of this year, 6.35% of all mortgages were behind in their payments, but foreclosure proceedings had begun on one in six of those. In the subprime markets, the delinquency rates are much higher (22% for variable rate mortgages), but the foreclosure rates are higher still (almost one in three). As late as 2002, the delinquency rates for this kind of mortgage were almost 15%, but only about one-sixth of the delinquent loans began foreclosures.

In other words, these are tough economic times, but at the ground level, we're not so far from other economic slowdowns. What's different now is that foreclosure is a far more likely outcome of falling behind in your mortgage payments than it has been at any time since HUD started tracking these numbers in 1986.

Why? Well, one reason might be that so many loans are held by speculators. National statistics from late 2007 (presented to Congress in January by the Mortgage Bankers Association) show that as many as a fifth of foreclosures are from investors -- people who have bought property not for its rental income, but simply to resell it for a profit.

When the mortgage broker doesn't require much of a down payment, and borrowing costs are low, then anyone with persistence can make money borrowing and investing. The stakes are low and the profits high. But with the stakes so low, there is little downside to abandoning a bad buy without trying to work out terms. Even in the high-flying and now-crashing world of high finance, this has been well-known for decades, even if the rules became easy to evade in recent years.

Practically speaking, the effect of the boom in housing speculation was to annihilate what little affordable housing we have in this state. Flipping properties is not perfectly compatible with having tenants (and rents didn't keep up with sale prices anyway) so lots of housing was withdrawn from the rental market. And because the poor neighborhoods in our state are where investors could find the best bargains, those are the places now suffering most from the continuing crunch in affordable housing. (Housing Works, an affordable housing advocacy group, just released their 2008 fact book, documenting how hard it is for a couple earning $74,000 a year to find affordable housing in Rhode Island.)

But even when you discount foreclosures to investors, the foreclosure rate is high. Why? Loans sold to investors as part of mortgage-backed bonds separated the lender and borrower by thousands of miles. When the borrower gets in trouble, there's no one to appeal to for a workout. Distant companies may have all the incentive in the world to work something out, but without a local contact people can talk to, they effectively have no ability to do anything but foreclose. Democrats in Washington have been calling for a year for action to help borrowers get workout terms where it's possible, but they've received nothing but a deaf ear until last week. Seems now like it would have been a good idea, doesn't it?

But this isn't all. Lots of households are, in fact, in trouble with their mortgages, but why? If you said that they took on mortgages they couldn't afford, you'd obviously be right, but perhaps only partly right. And what do you know? The HUD statistics show an increase in foreclosures in 2006 -- *preceding* the rise in delinquency -- but just after the Republican Congress passed bankruptcy "reform." The reform bill made it harder to go bankrupt, so that route out of financial trouble was shut down for millions of people, increasing the likelihood that people with troubled finances might just accept the trouble and walk away. The bill was pushed by the credit-card industry -- Barack Obama voted no and is on record wanting to overturn it, John McCain voted yes, even voting against an amedment to exempt bankruptcies due to medical bills. (And yes, Joe Biden voted for it.)

We're in a slowdown that began like others, but the legal and banking deck has been stacked against individual homeowners. That's what makes me want to throw my calculator at people who say this whole crisis is to be blamed on irresponsible borrowers. There's little or no evidence they've been more irresponsible than in the past, but the screws have been so tightened that more of them fail.

A hallmark of horrible public policy is a lack of concern for the failures. You see this all the time: we should close failing schools, flunk failing students, dump people off welfare who can't get a job, deny health care to immigrants (even legal immigrants). All these tough-talking policies are proposed by people who apparently imagine that the people, schools, whatever, will simply disappear. Proponents routinely deride those of us who want to accommodate the failures as softies. But here's news: they don't disappear. The people without health care overcrowd our emergency rooms, the failing students become unemployable adults, and apparently failed debtors can bring down our financial system. (Abetted, of course, by the geniuses of Wall Street.) A little more concern for the failures isn't evidence of a soft heart, but of practical minds.

15:06 - 04 Oct 2008 [/y8/cols]

Wed, 01 Oct 2008

Why did the bailout plan fail? Was it principled opposition or failed gamesmanship? from here:

The House conservatives who sank the bailout didn't do so because they were listening to loud and angry voices. They sank the plan by accident. They were trying to double-cross the Democrats. First, they wrung lots of concessions out of Democrats at the negotiating table as the price for delivering 80 votes. Then, by not delivering 80 votes and forcing Pelosi to pass the bill as a partisan Democratic bill, they were going to wage a demagogic anti-bailout campaign. But Pelosi refused to be played for a sucker and so the conservative inadvertently sank a bill that, all evidence suggests, they actually wanted to pass. They just wanted to vote "no" on it for short-term political gain.

As evidence for this view, it appears that the RNC prepared — in advance of Monday's vote — attack ads to be run against Democrats who voted for the plan.

As a philosophical point, there are two competing views of what politics is. Or at least there are two with which I am familiar. One view has it that politics is the process by which we rule our polity. This conception of politics is all about finding solutions to the problems we face. Another conception of politics is that it is war. In this conception, all the entities involved in politics are engaged in an all-out struggle for primacy and power. Which do you think serves our nation better?

10:50 - 01 Oct 2008 [/y8/oc]