What's this? A Book!

Or buy here: Light Publications, Powell's, or Bn, Amazon A look at the lousy situation Rhode Island is in, how we got here, and how we might be able to get out. Featuring

Now at bookstores near you, or buy it with the button above ($14, or $18 with shipping and sales tax). Contact information below if you'd like to schedule a book-related event, like a possibly entertaining talk on the book's subjects, featuring the famous mystery graph. Join the RIPR Mailing List! For a weekly column and (a few) other items of interest, click here or send an email to ripr-list-subscribe@whatcheer.net. RIPR is a (paper) newsletter and a weekly column appearing in ten of Rhode Island's finer newspapers. The goal is to look at local, state and federal policy issues that affect life here in the Ocean State, concentrating on action, not intentions or talk. If you'd like to help, please contribute an item, suggest an issue topic, or buy a subscription. If you can, buy two or three (subscribe here). Search this siteAvailable Back Issues:

Subscription information:

Contact:For those of you who can read english and understand it, the following is an email address you are welcome to use. If you are a web bot, we hope you can't understand it, and that's the point of writing it this way. editor at whatcheer dot net Archive:

AboutThe Rhode Island Policy Reporter is an independent news source that specializes in the technical issues of public policy that matter so much to all our lives, but that also tend not to be reported very well or even at all. The publication is owned and operated by Tom Sgouros, who has written all the text you'll find on this site, except for the articles with actual bylines. Responsibility: |

Sat, 27 Dec 2008

How much does it cost to live in Rhode Island? That's a hard question to answer, so here's another: how much do you have to earn so that you're not poor in Rhode Island?

Since it was first developed (by Mollie Orshansky, a researcher at the Social Security Administration, in 1963), the federal poverty level has been controversial, subject to misinterpretation and manipulation. Originally based on typical food budgets, the poverty level has crept up with food prices over the years, but not with the changes in the way we spend money, leaving it a poor measure of being poor.

If you're old enough, you'll remember a time in the 1970's when food prices were a political issue. Inflation, but especially food prices, defined economic concerns for many during that time. Spending about a third of your income on food was not unusual, and the poverty level was based on that.

Agriculture subsidies and policies to promote highly-efficient giant farms have driven down food prices ever since then, and so now food prices are not a political issue. (Except that these policies are the source of terrible environmental, labor and health consequences, but I'll save those for another time.) No one spends as much as a third of their monthly budget on food any more, but the poverty level -- officially about $1,460 per month for a family of three -- is still calculated off the food budget as if we did.

A more realistic measure is provided by the Poverty Institute, who has for several years compiled a state "standard of need." Essentially they have redone Orshansky's work, but using more realistic assumptions, and incorporating into the standard the various programs -- Medicaid, food stamps, and child care subsidies -- available to people who are poor.

And so they've found that if you're a single parent with two kids, you probably need to be earning more like $50,000 each year to be out of debt and have enough for the basic needs for you and your children. By "basic", I don't mean cable, either. We're talking about having enough to buy clothes and keep the fridge full, but no more. People who earn less are in trouble. For example, say you have a job paying $14.81 per hour. You're earning 175% of the poverty level, and about twice the minimum wage. Say you've found a real bargain of an apartment to live in, and have nothing but routine medical needs. Congratulations, with the subsidies for child care and Medicaid for which you qualify, you're probably only short about $50 every month.

Here's the catch: should you pick up some extra work, or be lucky enough to get an 84 cent per hour raise, you'll lose the child care and health care subsidies, and be about $1,100 in the hole every month. What luck. So someone who does everything right, and tries to get off public assistance, finds herself worse off than before. What this says is that our system is really nuts -- created as a response to the fantasies of politicians and talk show callers rather than to the real world. Motivated by the fear that someone, somewhere, might maybe get some aid he or she doesn't deserve, federal and state legislators have over the years created such an incredible mess of programs and eligibility regulations that irrationalities like this are the rule, not the exception.

I have on my desk a fascinating little book, called "Why Welfare States Persist" by Clem Brooks and Jeff Manza, sociologists at Indiana University and New York University respectively (University of Chicago Press, 2007). Their work asks why, in the face of budget cuts and right-wing backlashes in democracies all over the world, the components of the welfare state seem to survive. A common explanation they discuss is something you hear in Rhode Island all the time: powerful actors (such as unions) have seized control of programs in such a way to prevent the popular will from ending them. But given the decline in labor's political strength in many countries, and the persistence of labor-backed policies in those countries, it's a challenging case to make in a rigorous way. That is, it's easy to say, "It's all the unions' fault," but far harder to prove it in a world where pension givebacks and wage concessions are so common.

Brooks and Manza counter that you simply can't discount public opinion as a source of support for welfare state programs. Put simply, many of these programs are popular, and so they persist because this is a democracy, or at least something vaguely like one.

Popular? How can that be when you hear so much complaint about welfare, child care, Medicaid and the rest? But notice this: no one ever runs for office on eliminating these programs. I spent a fair amount of time reading Assembly campaign literature this fall, and I can't think of a single candidate who ran on *eliminating* a government program. Or at least none who would say so in public. Instead they'll say "we must do more with less" or something equally inane, or insist the programs are good, but need to be limited to those who deserve it. Depending on the candidate (and the audience) this might mean the white ones, the non-immigrant ones, or the ones who can find a job within two years while raising three children alone. This is an essentially dishonest approach, which is why I think it's worth looking at what politicians do instead of what they say.

People make mistakes, and bad things happen to good people, too. They deserve a system that can actually help them, not just one that allows us to pretend to help. You may say they shouldn't be "entitled" to that help, but many of us say we owe it to them. Enjoy your holidays this week, and please be generous, when you can.

14:09 - 27 Dec 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 20 Dec 2008

I got a press release last week from the Governor's office. It seems that he's organized what they're calling a small business stimulus package. Well that's the kind of thing we need right now, so I clicked right over and looked for the details.

Sadly, what was on offer was something else entirely: a package of measures intended to make it more likely that Rhode Island businesses who need credit will get it. Apparently the Governor's office organized a bunch of local banks to pledge specific dollar amounts in local business credit and a variety of other ways to get credit to small businesses. This is a good thing, and I'm glad it's happening. The measures, all told, are cheap ways to use the government's power to get things to happen. Credit is the life blood of many businesses, and current events in the financial markets have jeopardized it, even for businesses in no danger of default.

But what of this word, "stimulus?" I'm afraid it's become a little overused, sort of cheapened by wide use this year. What is stimulus?

Here's what it isn't: credit. During the 1990's, interest rates in Japan were essentially zero, and it didn't do diddly to get them out of their recession, because who wants to borrow money if there's nothing to invest in? Through the early years of our Great Depression, economists argued about why there were no good investment opportunities. Among the big guns, Harvard's Alvin Hansen duked it out with Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in economics journals and forums. They could agree that the problem was a lack of business investment and a lack of opportunities behind that. But both could only flounder around the reasons behind the lack. Hansen proposed that it was the inevitable result of the closing of the American frontier (which happened about a generation before, really). Schumpeter insisted that the welfare state had sapped Americans of their entrepreneurial drive.

Neither explanation won any prizes for coherence, and it was left to John Maynard Keynes to point out that the real cause of a lack of good investments is a lack of consumer demand for stuff. He said that controlling credit markets is like being on the end of a string. You can always pull the string to tighten credit (raising interest rates), and it will slow the economy down, but you can't push on the string. Easing credit won't stimulate anything, only create the conditions where stimulus can work. If you want to stimulate the economy, you need people to spend money. Stimulus is what makes businesses want to consume credit, but credit itself isn't stimulus. Providing credit is only leading the horse to the water, and has nothing to do with making it thirsty, let alone getting it to drink.

Rhode Island is a small state, with comparatively small resources. We can't stimulate demand in other places for products and services made here. But we can stimulate demand in our own local economy, and we'll do that by getting money in people's hands who will spend it here. What would be valuable stimulus now is money in people's hands that must be spent, not saved. Preferably spent locally.

We have some huge public works needs: roads and bridges, but also affordable housing and schools, which always seem to come at the end of those lists. There are high hopes that an Obama administration will provide significant funds for these kinds of projects, but even if projects are "ready to go" on January 20, few are likely to be underway before summer. The stimulus these provide will be useful, but slow coming.

For a quick jolt, a government can just hand out money, but that, well, has some problems. The federal government tried it earlier this year: gave us all a tax cut and told us to go spend. I don't know about you, but I let down my country and my "stimulus" check went right into savings. Stimulus is diluted when people save it instead of spending it. The best way I know around this is the way that Congressional Republicans nixed when it came up last year: give money to people whose lives dictate that they will spend it. Now is the time to expand the child care subsidy, or to extend unemployment benefits for example.

We also have to watch out for anti-stimulus. That is, here's what not to do: slash payrolls at our big employers. Of course, we're poised to do exactly that. The cities and towns are responsible for around 30,000 jobs in the state, and they're all making plans to cut back because of expected cuts in state aid and limits on their property taxes. But this is crazy. The state must keep them solvent, not just because of all the employees, but because of their suppliers: local businesses who need the business. But this apparently isn't on the menu.

Economists used to claim that natural forces would keep the economy at full employment. The Great Depression put an end to that talk, except among economists who choose to ignore it. What we learned was that the private sector alone can't do the job of getting us out of jams like that. Without government to push where it can and pull where it can, the economy can just putter along with hundreds of thousands of unemployed people.

But what are we here in Rhode Island going to get to address the slowdown? Apparently only ideas that cost nothing. The people in charge of your state have concluded that the state is powerless, and because they think so, it is. Tax cuts and low-interest loans didn't get us out of the Depression. As usual, the lessons of the past are right there out in the open, waiting for us. But they won't be used by people who are willfully blind to them.

15:57 - 20 Dec 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sun, 14 Dec 2008

Last week the Governor's "Blue-Ribbon Panel on Transportation Funding" issued its draft report about how we're supposed to pay for rebuilding our roads and bridges. The report says we need $639 million a year to rebuild our roads and bridges and to put RIPTA on a solid footing over the next ten years. This is about $285 million more than is going to come from the federal government or the existing array of taxes. This is a lot of money, even in these days of hundred-billion-dollar bailouts. It's enough dollar bills to blanket our sections of I-95 and 295 with them, including the breakdown lanes and bridge abutments.

The report isn't shy about revenue, which is a refreshing change -- not because I welcome paying more money, but because I welcome honesty from my public officials. It suggests a variety of tolls, taxes and fees to pay for the maintenance and reconstruction of what we've got. More about them in a moment.

The report recommendations are separated into the more frugal "Scenario 1" and the more expensive "Scenario 2". I gather that the intent is that we find some happy compromise between the two, but as I perused the report and its findings, I found it hard to imagine finding contentment anywhere between these two.

For one thing, only the expensive Scenario 2 envisions improving RIPTA service at all. Scenario 1 has it only that RIPTA gets to limp along at its current levels of service, removing only the constant sense of crisis.

Because it's the 21st century and because I remembered to charge my battery, I'm writing this on RIPTA bus 66, on my way home from Providence to South County. I'm sitting in the front, looking back, and I see two empty seats as we leave Providence, but we'll probably fill them up at the CCRI stop. The report proposes increasing the gas tax, and offers a "vehicle-miles traveled" (VMT) tax based on how many miles you drive in a year (part of Scenario 2), and suggests tolls on the interstates, too. I support policies that discourage driving, because driving is polluting, cars are expensive, and our roads are congested. But policies to discourage driving only make sense if there are alternatives. To raise taxes on driving without providing alternatives is what we students of government call really obnoxious public policy, and this is precisely what is envisioned by Scenario 1.

After that, I couldn't help notice that "frugality" is only for the suckers who ride the bus. I guess they figure we're used to it. For example, both Scenarios envision the complete reconstruction of the Sakonnet River Bridge. This project was originally introduced to us some years back as a choice between a $70 million repair job and a $170 million replacement. The replacement cost is now estimated at $210 million, but for the life of me I don't know why anyone would believe that number. The I-Boondoggle improvement to 195 was originally supposed to cost $150 million, and if you count the borrowing costs, its final tab will be closer to $1 billion. Do people imagine that cost inflation is only for bridges with funny names?

In other words, we're going to get another gold-plated replacement bridge, purchased on the basis of an unrealistic cost estimate, either way. Just what we need. Meanwhile, we only get better bus service in the unlikely event that the legislature agrees to the the whole menu of tax increases. (Note: We're at CCRI now, and the last seat is filled. Only one person standing, though.)

Then I looked closer at the tax proposals. The panel's intent was to make drivers pay for roads. This is an OK principle, but as usual, the details matter. Because all the proposed taxes are based on driving, none of them relate to the income of the people who have to pay them. So the owner of the '09 Jaguar will pay the same tax increase as the owner of the '92 Saturn.

In Scenario 2, the report talks about "redirecting" some funds from driving-related fees, like car sales taxes and registration fees, that currently go into the state's general revenue. Again, in a philosophical sense, you can see a good case for this kind of thing, but in a practical sense, they're suggesting taking money that is already going to help pay for educating your children and nursing home care -- not to mention the state police who patrol the highways -- which seems slightly presumptuous to me.

At this point, it's not at all clear if any of these proposals are going to go into the Governor's budget this year. He convened the commission, but is under no obligation to follow its recommendations. But the report will set the terms of debate over the budget this spring.

Meanwhile, that wasn't the only tax news of the week. Over at the "Governor's Strategic Tax Policy Workgroup", convened to discuss reforming the entire tax system, the "Individual Taxation" sub-group seems poised to recommend one of three alternatives for reforming our state taxes on individuals. Unsurprisingly, all three of the options involve substantially lower taxes on people at the top end of the income spectrum and all three will require people in the middle to suck it up and pay more.

This is perfectly in keeping with the business-first, trickle-down economics that has marked this Governor and this Assembly, so it should surprise no one. Come hell, high water, or global financial crisis, they will say tax cuts for rich people are the solution for all our economic ills. And if the state needs more revenue, to pay our bills in a responsible way, they'll suggest taxes so broad that they hit everyone, no matter their ability to pay.

Remember this when you're next told that "shared sacrifice" is how we're going to get through this financial and budget crisis.

15:01 - 14 Dec 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 06 Dec 2008

Affordable housing is still a problem

I was looking over some data about homelessness last week. It seems that the number of homeless people using shelters from July 2006 to June 2007 was about the same as the year, before, which seems like good news only until you compare it to the years before that. Shelter nights in 2006-2007 were up over 70% from 2000. The most recent year's data is still being compiled, but with unemployment up and rents not down, there's no obvious reason to think things have improved.

Homelessness is a complicated thing, with many reasons behind it, but high rents are a principal cause. Right now, the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment is about four times what a disabled person receiving Social Security (SSI) support receives. Sure, those people aren't necessarily shopping for median apartments, but show me the units that rent for $200 a month, which is about what they can afford. And that isn't the only problem.

During the crazy price run-up between 2000 and 2006 buying property in order to rent it became less and less feasible. From tax assessor data, I see that you could easily find a duplex in South Providence for between $225,000 and $280,000 in 2004. But the RI Housing rent survey from that year says that rents in the area averaged only around $750 or $800, not enough to cover a typical mortgage. The owners of these houses, where they decided to rent at all, had to push the envelope of the rental market.

According to RI Housing, the average rent in the state has gone from $750 in 2000 to $1175 in 2006, and then down to $1,142 in 2007. Meanwhile, the cost of an average multi-family home (statewide) went from $108,000 in 2000 to $285,000 in 2006, growing almost three times as fast. The prices have cratered since then, though it's a little hard to tell because the number sold in the poor neighborhoods of the state has soared compared to previous years.

What's more, because many landlords were buying only to resell, they were not that interested in tenants, preferring to apply new paint jobs and other cosmetic work to boost resale price. Tenants tend not to make a sale easier, so apartments stayed empty pending a sale. The practical effect was to withdraw a large number of rental units from the market. Rentals were expensive *and* hard to find during the bubble years.

Of course the downside to this kind of investment is that you don't want to be holding the ball when the music stops. A lot of foreclosures in the poor parts of our state have been investors walking away from deals gone bad by falling prices, leaving what tenants they have to be evicted by the bank. In a theoretical economics sense, this *is* the market correcting itself. The problem is that the corrections appear to take some time, and the human cost is pretty high while we're waiting.

Where does this leave us? In John Steinbeck's "Grapes of Wrath," he wrote about starving farm workers watching as surplus fruit was dumped on the ground and spoiled with kerosene to keep the fruit prices from collapsing. How different is that from where we are today? A homeless person walking over to Amos House in South Providence will pass more than a handful of boarded up and vacant houses on the way.

Figuring out what to do about this is not easy. It's clear that the market isn't working to provide housing to people who need it, but the only fix policy makers in our state have been behind is to build more affordable units. This isn't a terrible idea, and the people who get to live in them are made happy, but we can't possibly build our way out of the affordable housing crisis. The available money is too small and the market is too big. Reshaping the rules that govern that market is the only way we're going to put this behind us.

When you mention the possibility of regulating the housing market, many will gasp some economics pabulum about rent control. The evidence about rent control is much more mixed than most economists would have you know, but it's controversial and difficult to make it work right, and there is quite a lot we could try besides simple price controls. For example, making it harder to withdraw rental units from the market, or offering tenants a right to stay in their homes through a sale.

A more interesting possibility would be to privilege rental income and discourage speculation income. For years, our state has cut capital gains tax rates, to encourage investment. But the kind of investment this encourages (to the extent that it encourages any at all) is the buying and selling of enterprises and real estate, not the income derived from managing them. Our state does not suffer from a shortage of savings or investable funds, as the real estate bubble itself has shown us. Capital gains tax cuts solve a problem we don't have, and create revenue problems we don't need.

Let's instead lower the tax rate on income from residential rentals and help pay for it by putting the capital gains tax rates back where they belong, equivalent to the taxes on other kinds of income. According to IRS reports, RI residents earn about $190 million in rental income each year. Cutting the income tax in half on this would cost us around $5-6 million, far less than the capital gains cuts cost us. It would also be a great idea to enact an anti-speculation land gains tax, like they have in Vermont. This won't raise any revenue at all while we're still in the dumps, but I've lived through two housing bubbles in the past 20 years, and that's quite enough for me, thank you very much. Now is the time to ensure that we don't have to go through it all again.

18:26 - 06 Dec 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 29 Nov 2008

Last week I attended the monthly Geek Dinner at AS220 in Providence, a regular get-together for anyone interested in Rhode Island's tech industry. I got there early enough to get a seat and sat at a table with a guy who runs a database business and who is thinking about a new venture that -- well it would be unkind to describe his business idea, since I was talking to him as a fellow geek, not as a reporter. But it was great, and I would buy it, so I hope he goes ahead with it.

The evening's speakers were from DandyID.org, and they have a proposal for unifying your online identities across different services, so that your Facebook identity matches you on Amazon and Twitter, too, along with about 150 others. This way, your friends on one service can find you on another, and you can save having to maintain all these separate identities. It's an interesting niche, but what caught my attention is the three partners just moved their company here from Boulder, Colorado, a place I'm more accustomed to hearing about moving companies to.

I spoke with Sara Czyzewicz, one of DandyID's three partners and she told me that Boulder is oversaturated with startups, which makes it hard to get actual employees, and it's quite expensive to get space. They toured places like Seattle and San Francisco last year, looking to move. They added Providence to their list, and were quite surprised when they got here. (Sara is originally from Pawtucket though her partners are not.) She said they were attracted by affordable office space, but also by events like the Geek Dinners, and efforts like RI Nexus which show off the active community of technologists and inventors they found here. Since arriving in August, they've settled down to their new routine, and have found themselves a new programmer, too.

Perhaps this isn't the kind of story you expected in the paper this week, now that unemployment rate is approaching 10%? I believe our problems are best solved by a frank assessment of the situation. I've written plenty already about how the state's budget fiasco was the completely avoidable result of bad policy choices. Honesty about this is important, but it's equally important to see the good, such as it is.

One of the astonishing features of politics in Rhode Island is the prevalence of what can only be called a sort of civic self-loathing. For reasons that elude me, many of my friends and neighbors, and many of the state's policy makers are perpetually ready to believe the worst about our state: it has the highest taxes, the most corruption, the highest costs, the worst economy. If you read the news, you know the drill.

Much of this, though, is silly. People who think we've cornered a market on corruption have obviously never heard of Queens. (Or seen Chinatown, Roman Polanski's masterpiece.) Or read the papers in places like Philadelphia, San Diego, or Anchorage. We had a corrupt governor go to jail? Well so did Connecticut.

The highest taxes? Please. New Hampshire is a tax haven, right? Some of it is, but if I were to move from my home here to a comparable house in Jaffrey, Keene, Peterborough, or any equally unfashionable town, my total taxes would increase even without a sales or income tax. Our state and local taxes are lower than the national average, according to the Tax Foundation rankings whose poor methodology actually exaggerates the impact of our income tax. (We rise to 10th in their rankings only when they add the taxes you and I pay to other states, I kid you not.) There are at least 27 other states with higher sales taxes for at least some of their counties than we have. We have high property taxes, yes, but can you fix that by level funding the cities and towns while piling on new mandates?

The worst economy? Yes, it's bad now, like everywhere. But here's some news: we're small and urban. If you compare us to less urban states, we look bad. If you compare our urban area to other urban areas, not so much. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are 42 urban areas in 12 states doing worse than we are. This is still pretty terrible, and unemployment is way too high for anyone to be complacent, but we've got to get it out of our heads that it's something unique to us.

The worst deficit in the country? OK, this one's right. But why is our deficit so bad? It's because so many policymakers have convinced themselves that our state is so hopeless the only thing they can do is lower our price. And so they cut taxes and cut and cut some more, way past the point of sustainability.

There's a bargain implicit in any government's relation with its citizens: we give taxes and get services. For years, Assembly leaders and Governors have tried to improve the bargain by focusing on only the first part of that equation.

This shortsighted perspective, and the determination to pursue it at all costs, has thoroughly ruined the service side of the equation, and given us the worst of both worlds: devastated services and higher state and local taxes. Bankrupting the state is not a route to prosperity.

We are a relatively poor state and proportionately very urban. We may not ever be able to be a low-cost state, but that doesn't mean we can't compete, as DandyID shows. We have other high cards: a beautiful state, a hip capital city, a fabulous art scene and more. What we don't have is policy makers willing to play them.

Oh, one more thing: DandyID.org is looking for a PR person who can really write and is habitual user of multiple social networking sites. If you have to ask how to contact them, this job isn't for you.

14:54 - 29 Nov 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 22 Nov 2008

The state budget chickens are coming home to roost. After five years of self-inflicted fiscal crises, we finally have a real one, and your state is pretty much helpless. You might remember all the fuss last spring about closing a $400 million deficit in this year's budget. That was the manufactured crisis, created by years of ill-advised tax cuts, deferred maintenance and a refusal to raise enough money to pay our bills.

But now we face a real crisis. Last week the Revenue Estimator Conference met and agreed that we're going to be short around $233 million from what was estimated last May. We're also spending more, for nursing home care, RIte Care, DCYF and other services. The Governor's office says the overspending plus the shortfall totals $372 million, though I expect that number to change.

It's not as if we haven't been cutting. This fall saw a tidal wave of retirements as people who were eligible rushed to get out the door before their health benefits were lost. I've met lots of people in the last few months who weren't really ready to retire, but felt they had little choice. One retirement party I attended was more akin to a wake, really. The result of it all is that many more people retired than were anticipated. The Governor's budget predicted that about 1000 people would retire, and that we'd replace about 400 of them. In the event, more than 1700 people left state service, and so far we've only replaced about 150, according to the Governor's office. That means we've cut one employee in ten, across the whole state government.

Sounds good? Well, we've seen this dance before, under Ed DiPrete. Here's how it goes. First, enjoy the savings this year, because next year, the combination of a wave of retirements and a lousy year on the stock market is going to drive pension costs up through the state house dome. Woe to the cities and towns, too, whose teachers are in the same pension system.

Second, a lot of the savings are illusory. The administration continues to maintain that we are going to see no cut in services due to this exodus, but it's hard to see how this is possible, especially with further cuts coming. Every rock I turn over shows me another department running on fumes. I hope you don't expect any maintenance to be done this year on state facilities, or for your unemployment claims to be processed any quicker.

On the other hand, I hear (again from the Governor's office) that we've been running "Six Sigma" workshops for department managers all over the state, to teach them how to do more with less. Apparently we'll have Six Sigma "green belts" and "black belts" running the DMV and DOT. I'm sure that will help.

Meanwhile, over on the revenue side, it may interest you to know that if you earn more than $250,000, we are offering you as much as an 18% cut in your income tax over last year, due to the "flat tax" option. What's more, this spring we're going to borrow almost $300 million in order to pay off the rich people and companies who hold historic tax credits. About $60 million of that was never used for building renovations, but is pure profit for those people.

One thing to watch for is that over its first couple of years, the flat tax cost us less than anyone (including me) had anticipated. One reason was that the historic tax credit offered a bigger cut from many people's taxes, and the rules say taxpayers can't take both. But now that the historic tax credit is over (and some historic renovation projects may not be happening, either) watch for the cost of the flat tax to shoot up, though we won't really know until the tax returns start coming in.

There are no good choices ahead. One thing is clear, though. If you want your government to *do* something to help in the current crisis, tough luck. You wanted better bus service, heating assistance, improved roads, rebuilt schools? Would you like to see the state make a push to creating green jobs? Perhaps you might have hoped we could put some construction workers to work insulating houses, or find boatbuilders to build windmill blades? Check in again in a few years. Rather than be an aid to its citizens, your state government is perfectly positioned to drag the whole state down a little further.

Most of the tax cuts that put us in this terrible position were made in order to promote investment in our state. But the idea that we have a capital shortage here borders on the absurd. If you imagine capital is in short supply, then help me understand exactly what it was that caused the housing bubble. No, the evidence is that we have not a shortage but a glut of savings, but it's not allocated in a way that helps our economy grow. After all, finding good productive investments is hard.

Government could play a role here, not just in matchmaking, or trying to increase the supply of capital, but (for example) in actively trying to shape the investment market. We could be using taxes to discourage some kinds of investment in order to favor others. We could be facilitating the formation of capital pools for local investments. We could be finding ways to pressure the big interstate banks to service the credit needs of local businesses. But your state government isn't going to do any of that. On the other hand, for 95% of the people reading this, if all you really wanted was smaller government at about the same cost as the old one, this is your lucky year.

21:41 - 22 Nov 2008 [/y8/cols]

Fri, 14 Nov 2008

In War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy created an absorbing story about how individual actors created the events that shaped European history, but how none of them were ever knew what was going on when they did. Napoleon won battles during which no one followed (or even received) his orders, and yet was credited with strategic genius for those victories. Weather and disease lost other battles (and the war) and Napoleon got the blame. In Tolstoy's view, the sweep of history is nothing more than the story of individuals blundering about, doing the best they can with their limited views of circumstances, and grand generalizations about it all are just hot air.

The opinion pages of our state's newspapers are routinely filled with exactly these kinds of grand generalizations, facile words describing how our state's politics can be explained because voters have "chosen" the status quo, or "refuse" change because they re-elected so many members of the General Assembly.

I'm with Tolstoy on this: it's silly to encase the individual acts of hundreds of thousands of people in some kind of frozen metaphor like "the people want..." It doesn't explain anything and besides, in our government, "the people" have no way to express "their" opinion. If you are reading this, you probably have opinions about how the state would be best served. When you were in the voting booth last week, did you feel that any of the choices on offer represented your opinions well? The fate of our state deserves at least an essay question, but elections are multiple choice tests. Actually, given how many candidates run unopposed, many elections are True/False tests, where you're not allowed to check "False."

So, given all that, can we learn anything from the state election results of last week? Studying the results, the best I could come up with was this: when given the option, voters often seemed to prefer new faces, but not Republicans. Where elections were about policy issues, progressive views seemed to prevail. Mostly.

That's not much of a lesson, really, but it does lead to some interesting questions about the Republicans, who lost almost half their General Assembly seats, bringing them down to four Senators and six Representatives, the lowest number in decades. For the most part, the new faces the state Republican party introduced to us were an unimpressive group of radicals, and most of them lost.

In other countries, this kind of electoral catastrophe brings about a realignment, as new parties form to fill the void left by political failure. Why not here? It's not as if people aren't trying. Businessman Ken Block has organized the "Moderate Party." Their name is more a sign of our times than an accurate description, since their platform is basic Republicanism, albeit of a generation ago. Robert Healey's Cool Moose party gave it a shot in the 1990's, too, but didn't get much traction, maybe only because he doesn't look like a Republican. But these are efforts to organize outside the Republican party. Efforts within haven't gone anywhere that I can tell.

But all is not bleak. There were two notable Republican winners, last week. You didn't hear about them? Baker Michael Pinga unseated Senator Stephen Alves of West Warwick and Ed O'Neill of Lincoln trounced Senate President Joseph Montalbano. You might have overlooked them because in order to win, they abandoned their party and ran as a Democrat and independent, respectively. And here's the real rub: Conservative as both of them are, they will find many compatible colleagues among the Democrats of the General Assembly.

The failure of the state Republican party is a failure to recognize that there is demand for a constructive and conservative party here. Sadly, state Republican leaders refuse to supply that demand. Governor Carcieri seems to relish spending his time bashing immigrants, unions and advocates for the poor on the radio even while candidates who concentrate on those issues lose. Meanwhile Pinga and O'Neill, who appear to approximate old-time yankee Republicanism, did just fine.

What can be done? Look to Minnesota, where there is no state Democratic Party. That state's affiliate of the national party is officially the "Democratic-Farmer-Labor" party, a linguistic vestige of a long-ago merger when moderates captured control of the Farmer-Labor party after electoral losses and merged it with the weaker state Democratic party. The Rhode Island Republican party could benefit from something similar. That is, someone needs to rescue it from the radicals currently in charge.

Here's my suggestion for those potential rescuers: Stop running on nonsensical solutions to hot-button social issues -- Throw all the immigrants out! End all abortions tomorrow! -- and the cartoon version of the legislature. Stop governing as if tax cuts are the answer to every single issue. Fiscal responsibility used to be a Republican virtue, and responsibility means paying your bills. (John Chafee sacrificed his governorship to pass the income tax.) Paint us a real picture of our state and offer real solutions. It is possible to do this from a conservative perspective, honest. Change your name to the "Yankee Republicans" and differentiate yourselves from the fanatic Republicans of the Southern and Western states. Offer us a real, sensible, choice in elections, and I predict that not only will voters appreciate it, but you'll be able to recruit better candidates, and maybe even turn some coats in the Assembly. I'm not the first to say our state would benefit from better choices on our ballots, but it now seems clear that we're not going to get them from this Republican Party.

23:24 - 14 Nov 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 08 Nov 2008

I had to write this column last week, and my crystal ball was cloudy, so not a word about the election today, but in the spirit of changes afoot, I have a couple of pieces of good news worth sharing -- your government succeeding by doing interesting and creative things.

The first concerns the state bond sale of a couple of weeks ago. This was when Treasurer Frank Caprio arranged to sell bonds to the public. Here's what happened.

The state had to sell around $350 million in short-term bonds, paid off by next June. The professional bond buyers are all having heart palpitations these days, and when they're calm, they're quoting rates double and triple what the state has budgeted. Bond projects with discretionary time schedules are all being put off until things calm down. But these tax anticipation notes are all about cash flow. The state can't put them off and still make payroll.

On the other hand, a lot of the turmoil on Wall Street has no reasoning behind it. The State of Rhode Island, for all its flaws, is no more likely to go out of business and default on its bonds than it was last year or the year before. In other words, there is really no reason a bond buyer should demand a higher rate from Rhode Island, except if they're afraid they won't be able to sell them to someone else. It's a perception problem more than anything else.

Perceptions can be dealt with. First, the Treasurer's office arranged to sell bonds directly to the public on Monday. They were available through brokers, but also through a few Bank America branches. Second, they scheduled a bond auction in New York the same day, but held until lunchtime, and identified the likely bidders (and pestered them all weekend to make sure they showed up).

Then Monday morning came, and we sold around $25 million of bonds to retail customers, through bank branches and local brokers. The phone traffic was fairly heavy, and there were reports of decent-sized lines at some of the branches. So all morning the Treasurer's office duly sent notes to the potential bidders that hordes of buyers were clamoring for these bonds. (In a relative sense, of course, that was true.)

And what do you know? All those hard-headed Wall Street business types whose job it is to put emotions aside and make cold, calculating trading decisions completely lost their cool, breathed a sigh of relief and bid the price of the bonds higher than anyone expected (holding down the interest rate), thereby proving what you already knew: those business types may wear better suits than you, but that's about the only difference.

The other spot of good news? Riverwood Mental Health Services established a program called "Housing First" a couple of years ago. The idea was that about 15% of Rhode Island's homeless population is homeless because of mental health or substance abuse issues, but that providing services for those issues in shelters and while people are living under bridges is kind of a losing proposition. Treatment programs for this population think of 40% success rates as a distant goal, but the best will make do with 20% or less and call it a triumph.

Housing First takes a different approach, and provides subsidized housing for clients without strings. The housing comes with intensive drug treatment and mental health services, but it isn't forced on them. They can choose to avail themselves of the help, or not, but they don't get kicked out if they say no.

Lo and behold, few say no. After over a year of the pilot program, 90% of the clients are still in their housing, and most are participating in various forms of treatment. The clients had been homeless for an average of over 7 years, but are now finding their feet. The stories range from children reconciling with long-lost parents to folks just finding it possible to get back on their feet.

It's not just heart-warming stories, either. According to an independent study by Eric Hirsch and Irene Glasser, professors at Providence College and Roger Williams, respectively, the program is a less expensive way to deal with the chronically homeless. Compared to their own experiences in the previous year, the clients of the program were in the hospital fewer nights, in jail fewer nights, in treatment fewer nights and so on. Some will roll their eyes and talk about the "moral hazard" of giving things away to drug addicts, but the truth is that, per year, we spent almost $8,000 less money (per person) on these people by giving them homes than we did when they were left out on the street. The good news is that Riverwood was just awarded $2 million from the US Department of Health and Human Services to double the scope of the program. Riverwood was one of only twelve similar programs in the country to be recognized.

As I've said in the past, a hallmark of poor policy is the assumption that the "losers" need no attention. People with mental health issues or substance abuse problems do not evaporate just because we've averted our gaze. They stick around, and we pay for them, one way or another. You don't have to be soft-hearted to think that providing them with a home and services is a better way to deal with their problems than turning a blind eye.

10:09 - 08 Nov 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 18 Oct 2008

So there are exciting times on Wall Street. But what does the financial crisis mean for those of us who aren't borrowing or lending? Well, the credit markets serve not just businesses but governments, too.

Our state and local governments issue bonds not just for building things, but also for cash management. That is, sometimes the tax revenue doesn't come in synch with the bills to be paid. In those cases, cities and towns can issue "tax anticipation notes", short term loans to help cover the bills until the tax collections pick up. It's a pretty typical cash management technique. Borrowing for a few months at 3% isn't a huge cost, and if it means not having to build up a big cash reserve, so much the better.

But this only works so long as the credit market works and the rates are low. East Providence has used anticipation notes fairly routinely in the past, and was intending to do so this fall. Last year they borrowed about $25 million at 3% interest sometime in December, and paid it back when property tax collections started arriving in the summer. They anticipate about the same need this year, but at the moment, interest rates are running at more than triple what they've paid in the past, not to mention some uncertainty their bonds would sell at all. Right now, their policy is to hope this all clears up by December since they only have around $4 million in reserve. If it doesn't, there's big trouble.

The state frequently uses anticipation bonds, too. But they skipped a prospective issue this month, and borrowed from the TDI fund instead. This isn't such a bad idea, really, since the fund itself is going to have some trouble finding decent investments in the near future. The state will pay interest at a rate comparable to what the fund would be able to get.

But though the state has resources it can use to insulate itself, it it's hardly immune to the credit market freeze-up. A scheduled bond sale by the Clean Water Finance Agency will be put off until next year. This agency provides funds for cities and towns to make improvements to their waste-water and drinking-water systems. Among others, North Kingstown is planning to deal with lead contamination issues at two of its wells, and Newport has some dam repair projects as well as improvements to its storm-water sewer system pending. All told, around a half-dozen cities and towns have around $45 million in projects about to begin that depend on funds from the CWFA.

CWFA has cash reserves from previous projects, so is able to provide bridge loans to the cities and towns it serves until the bonds can be sold. In a related move, North Kingstown has signed contracts for constructing a new senior center, so they're moving ahead using funds from their budget reserve, even though the $4 million bond sale to cover the costs will be put off. If the markets recover soon, moves like these will seem smart. However...

The open market is one of history's most impressive achievements in allocating resources. Among a zillion other cool feats, the market for money itself has created a way to streamline governments by allowing them to tap a vast pool of investment funds to help manage their cash flows and invest in infrastructure projects.

But this is true only so long as the markets function well, and cheaply. We now know that this isn't a law of nature. None of us know how this turmoil will settle out, but it's fairly likely that government borrowing for routine infrastructure projects is going to be harder and more expensive than it has been. Even once sense is restored to the market for state and local government bonds, the pool of money from which they'll draw and the number of willing lenders is going to be smaller.

Here's another safe bet: With a number of commercial banks near failure and with a dwindling number of safe places to keep one's money, it's going to be a long time before the interest on bank accounts is anything more than nominal.

A state-run infrastructure bond bank might be a way to solve both those problems. Done right, this would be a way for any citizen to use a savings account to invest in improvements in their own community. In return, they'd have a safe place to keep their money, at decent rates (tax-free, too). Right now, our national markets price bonds from anywhere absurdly low because faraway bankers have no idea of their value. But the market isn't always right; people who live in a town or a state not only have a sense of its value, but also a stake in it.

Proposals like this have been met in the past with imputations of socialism. I heard this with my own ears, for example, one winter day in 1991 when I was wandering around the statehouse trying to interest General Assembly members (and anyone else who would listen, frankly) in a proposal I'd written up for a state-run infrastructure bank as a solution to the credit union crisis. But -- thank you Henry Paulson! -- now that you and I are part owners of a huge insurance company and soon some banks, too, I have a much more effective comeback to this kind of inane critique than I did back then.

Over the next few years, after we're done reeling from this financial shock, we're going to need all the good ideas we can find in order to get back up again. Idolatry of the free market has got us into this mess. Let it not complicate the business of getting us out, too.

00:47 - 18 Oct 2008 [/y8/cols]

Fri, 10 Oct 2008

Sometime during the Ford administration, legend has it that Wall Street Journal editor Jude Wanniski and two White House officials named Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney sat down for lunch with the economist Arthur Laffer. During the meal, Wanniski said Laffer drew the famous "Laffer Curve" on his napkin, and our government has never been the same since.

The Laffer Curve? That's a graph that shows that if you raise taxes too high, tax revenue drops. Conversely, if you're above some magic point on the graph, lowering the tax rate will increase revenue.

But the whole thing is essentially a fairy tale, beginning with the napkin. As Laffer himself told it, the restaurant had cloth napkins and "my mother had raised me not to desecrate nice things."

But what about the economics? In a certain sense, of course, the Laffer Curve is valid, even obvious. In an abstract world, it is indeed possible to imagine a tax high enough that raising it further would lower revenue. However, stepping back into the real world, few real governments could actually impose such a tax. Ours never has, and despite legions of economists looking for examples, no one has ever demonstrated that this effect is observed in the world in which you and I live.

You'll hear people who've drunk the supply side Kool-Aid say that the Kennedy tax cuts or the Reagan cuts or even the Harding-Coolidge cuts were good examples, because tax collections increased after they were enacted. But all of these cuts were accompanied by massive increases in government spending or the end of a recession or the end of punitively high interest rates or some combination of the above that turned out to be much more important effects. The toothlessness of Nixon's 1971 tax cuts never seems to come up.

However, imagine that it were possible to prove that some tax cuts have actually increased revenue. Even so, Laffer himself never suggested that tax cuts *always* raise revenue. And yet, reviewing some literature and web sites for candidates to the General Assembly this past week, it seems that a number of them believe exactly that. Of course, this is the dominant point of view at the state house, where the only economic plan offered in the past several years is for yet more tax cuts. So if elected, they'll feel right at home.

I sent a note to Steven Hart, a Republican running for state Representative in District 28 (Coventry), who wrote on his web site that "crippling tax increases" had damaged our economy. Since the last increase in a broad-based state tax was 15 years ago, I wrote to ask what he meant. He wrote back that "Lowering the [corporate income tax] rate would attract businesses to locate here which will provide additional tax revenue and create jobs..." Well, perhaps.

Much more straightforward was the approach of James Haldeman, another Republican running in Wakefield (District 35). He wouldn't tell me what he'd cut from the budget in order to cut tax rates: "My emphasis is on reducing tax rates! If we lower tax RATES significantly (on business and the individual) we will actually generate more tax RECEIPTS." [his emphasis]

Let's go to the numbers. The corporate tax is 9% of income and is paid by about 2,500 corporations. Not counting the companies who pay the $500 minimum (44,000 of them!), this tax raised $134 million in 2007. Were we to trim it to 8%, we'd need to raise $14 million in new revenues to make the cut pay for itself. Counting income and corporate taxes, that's the equivalent of 130 new companies with income of around half a million each, and with an average payroll of more than $2 million. Do you think this is a likely outcome of a small cut in one tax?

What about the income tax? Rhode Islanders earn around $40 billion a year these days. Out of that, we pay about $1 billion in income tax each year. In order for a 5% cut in the income tax to pay for itself, it would have to cause a 5% rise in personal income, roughly equivalent to the growth rate in 2003 and 2004. But ask yourself: what effect would a 5% cut in your state income tax have on you?

If you're part of a family earning around $75,000, a 5% cut in your income tax will be worth around $100. That's going to net a lot of economic stimulus, isn't it? Maybe you expect more rich people to move in, or put your hopes on the merchants and tradespeople they pay to re-spend the money they receive (the "multiplier")? Well, if we were actually an island, if nobody put their tax cut in the bank, if everyone spent it all as fast as they could on local businesses *and* if five hundred really rich people moved in because of the cut, then there'd be a fighting chance of making it pay for itself. Maybe. A larger cut would require a larger effect. Applied to the real world of Rhode Island's taxes, the whole proposition is completely absurd, but it so often comes masked in economic gobbledy-gook that people are routinely taken in.

Here's the bottom line: lower state taxes means less state revenue. You may think that's just fine, or you may not. Either way, don't trust candidates like Hart or Haldeman who promise the utterly impossible. Make them say what they'd chop for their tax cuts. Faith in the impossible has brought our state to a position where we have the wherwithal to do just about nothing in the face of the economic crisis facing us. Our fiscal crisis is going to get worse before it gets better and believing nonsense is not going to help one bit.

23:03 - 10 Oct 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 04 Oct 2008

A Failure to Plan for Failures

As the nation continues to reel from the ongoing financial crisis, the boom and bust that we're suffering, it's worth stopping to ask how it is that we got to this place.

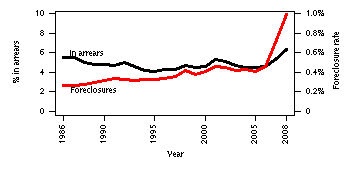

Everyone knows that foreclosures are driving the economic crisis, but does everyone know that people falling behind in their payments isn't the big story? According to HUD statistics, in 1986, about 5.5% of all mortgages were in arrears, and about one in 21 of those went into foreclosure. In the first quarter of this year, 6.35% of all mortgages were behind in their payments, but foreclosure proceedings had begun on one in six of those. In the subprime markets, the delinquency rates are much higher (22% for variable rate mortgages), but the foreclosure rates are higher still (almost one in three). As late as 2002, the delinquency rates for this kind of mortgage were almost 15%, but only about one-sixth of the delinquent loans began foreclosures.

In other words, these are tough economic times, but at the ground level, we're not so far from other economic slowdowns. What's different now is that foreclosure is a far more likely outcome of falling behind in your mortgage payments than it has been at any time since HUD started tracking these numbers in 1986.

Why? Well, one reason might be that so many loans are held by speculators. National statistics from late 2007 (presented to Congress in January by the Mortgage Bankers Association) show that as many as a fifth of foreclosures are from investors -- people who have bought property not for its rental income, but simply to resell it for a profit.

When the mortgage broker doesn't require much of a down payment, and borrowing costs are low, then anyone with persistence can make money borrowing and investing. The stakes are low and the profits high. But with the stakes so low, there is little downside to abandoning a bad buy without trying to work out terms. Even in the high-flying and now-crashing world of high finance, this has been well-known for decades, even if the rules became easy to evade in recent years.

Practically speaking, the effect of the boom in housing speculation was to annihilate what little affordable housing we have in this state. Flipping properties is not perfectly compatible with having tenants (and rents didn't keep up with sale prices anyway) so lots of housing was withdrawn from the rental market. And because the poor neighborhoods in our state are where investors could find the best bargains, those are the places now suffering most from the continuing crunch in affordable housing. (Housing Works, an affordable housing advocacy group, just released their 2008 fact book, documenting how hard it is for a couple earning $74,000 a year to find affordable housing in Rhode Island.)

But even when you discount foreclosures to investors, the foreclosure rate is high. Why? Loans sold to investors as part of mortgage-backed bonds separated the lender and borrower by thousands of miles. When the borrower gets in trouble, there's no one to appeal to for a workout. Distant companies may have all the incentive in the world to work something out, but without a local contact people can talk to, they effectively have no ability to do anything but foreclose. Democrats in Washington have been calling for a year for action to help borrowers get workout terms where it's possible, but they've received nothing but a deaf ear until last week. Seems now like it would have been a good idea, doesn't it?

But this isn't all. Lots of households are, in fact, in trouble with their mortgages, but why? If you said that they took on mortgages they couldn't afford, you'd obviously be right, but perhaps only partly right. And what do you know? The HUD statistics show an increase in foreclosures in 2006 -- *preceding* the rise in delinquency -- but just after the Republican Congress passed bankruptcy "reform." The reform bill made it harder to go bankrupt, so that route out of financial trouble was shut down for millions of people, increasing the likelihood that people with troubled finances might just accept the trouble and walk away. The bill was pushed by the credit-card industry -- Barack Obama voted no and is on record wanting to overturn it, John McCain voted yes, even voting against an amedment to exempt bankruptcies due to medical bills. (And yes, Joe Biden voted for it.)

We're in a slowdown that began like others, but the legal and banking deck has been stacked against individual homeowners. That's what makes me want to throw my calculator at people who say this whole crisis is to be blamed on irresponsible borrowers. There's little or no evidence they've been more irresponsible than in the past, but the screws have been so tightened that more of them fail.

A hallmark of horrible public policy is a lack of concern for the failures. You see this all the time: we should close failing schools, flunk failing students, dump people off welfare who can't get a job, deny health care to immigrants (even legal immigrants). All these tough-talking policies are proposed by people who apparently imagine that the people, schools, whatever, will simply disappear. Proponents routinely deride those of us who want to accommodate the failures as softies. But here's news: they don't disappear. The people without health care overcrowd our emergency rooms, the failing students become unemployable adults, and apparently failed debtors can bring down our financial system. (Abetted, of course, by the geniuses of Wall Street.) A little more concern for the failures isn't evidence of a soft heart, but of practical minds.

15:06 - 04 Oct 2008 [/y8/cols]

Wed, 24 Sep 2008

Over the past 25 years, as our nation has disassembled its manufacturing base and shipped those jobs elsewhere, we've heard over and over again about how that's ok, because those kind of "old economy" jobs were the thing of the past and the "new economy" would provide lots of jobs in finance, service, software, design, and management. We were all supposed to become "knowledge workers", according to Peter Drucker. In the new economy assets are "minds rather than machines," said George Gilder. The new economy was to be clean, smooth and prosperous.

Admittedly, we haven't heard much about all this lately. Gilder's newsletter and web site empire collapsed after the technology stock crash in 2000-2001. Some of the other cheerleaders have gone to ground, while others have said they were right all along -- about different predictions. But the truth is that the events of the past year, and especially the past week, have made everyone a little skittish about imagining an economic future that depends on finance. (Except securities lawyers, who are going to have a little boom of their own over the next few years as the sub-prime mess gets untangled.)

The other parts of the new economy order are cause for concern, too. Service jobs are, in general, not the kind of high-wage jobs around which much else can be built. The software industry is still not a bad bet, but as big as Microsoft is, the whole industry is still a tiny fraction of the US economy. Combining computer manufacturing, data processing services and software, we're talking a bit less than 3% of the US economy.

So, if the new economy really isn't the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, and we've already given away most of our manufacturing jobs, what's left? One answer is to look ahead at some new markets that are developing.

In the early 1980's, I worked at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, on issues related to global warming. (We called it the greenhouse effect back then.) At the time, there was little controversy I noticed about whether the effect was real or whether it was manmade. Those were settled issues. The research I helped with (partly funded by oil companies) was all about trying to characterize the rate at which processes on which warming depends can be expected to happen. Now, 26 years later, there's a certain gratification in seeing that what was widely accepted in the world of oceanography back then is gradually gaining acceptance in the rest of the world. Of course the gratification is tempered by astonishment that it's taken so long, but better late than never, I guess.

But now that global warming is on enough people's minds, what can we do about it? And why did the subject change to global warming? Weren't we just talking about manufacturing and the economy?

Well, it's possible that the two subjects can be the same subject. As more and more people become aware of the need to reduce our reliance on carbon-based fuels, it's pretty natural to expect that the demand for wind and solar energy equipment and whatever else comes along will rise. As heating fuel costs go up and up, the payoff for insulating your house gets shorter and shorter. As electricity prices rise, so does the appeal of solar electric panels. The more expensive gas gets, the better-looking one of those electric cars gets.

All of these factors mean that there are opportunities ahead for mechanics who learn how to fix electric cars, for insulation contractors, for shops who can build and market wind turbines, and for companies who will exploit technologies we haven't even thought of yet.

To the extent that these "green" jobs of the future are service jobs, few will be exported to China (you can't ship your front wall over to China for insulation), and to the extent that they're new technologies, they will be fertile ground for entrepreneurs to find and exploit new opportunities quickly.

In 2007, Congress passed the "Green Jobs Act", also known as Title X of the 2007 Energy bill. The bill passed, and is intended to create job-training programs for green jobs, but it's stalled now, while Congress decides whether to fund it or not. Funding this will help, though it's only a beginning. The Federal government provides tremendous subsidies and tax credits every year to the oil, gas and coal industries, and to various aspects of the construction industry, too. These subsidies should be re-engineered to promote the development of the technologies we'll need if we're going to turn back the tide, so to speak. In a state with as much low-lying swamp as we have, this is speaking directly to our future.

This coming Saturday, the 27th of September, from 9:30 to 11:30AM, there will be a conference about "Greening the Rhode Island Economy" at the New England Institute of Technology, 2480 Post Road in Warwick. (The RIPTA service cutbacks haven't hit yet, so the number 14 bus goes right by, even on Saturday.)

Part of a larger national day of action organized by dozens of organizations in a coalition called "Green Jobs Now", the event will have its keynote address from Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, introduced by Providence Mayor David Cicilline. There will be short talks by economists and people working in job training, as well as construction industry representatives and more. The idea is both to educate people who want to learn more about what might be possible in a world with more green jobs, and to pressure Congress to fund the Green Jobs act, and take the next step beyond that. Join us, please.

The event is free, but the organizers ask you to please register at www.GreeningRIEconomy.com.

22:47 - 24 Sep 2008 [/y8/cols]

Sat, 20 Sep 2008

A couple of weeks ago, Bill Connelly, a candidate for state senate district 36 in North Kingstown and Narragansett, handed me a flyer. I put it in my pocket, and checked it out when I got home. It had a nice picture and capsule bio. For policy planks in his platform, it had only four bullet points. I was particularly interested in two: One said, "Increase state aid to education" and right after it was, "Hold the state to spending and taxing limits."

Well, golly, when you put it like that, it sounds pretty good. Easy, too. I mean why didn't anyone think of that before? But why stop there, let's just eliminate all taxes and make the schools better, too. Or maybe offer us all free commuting helicopters? Better yet, free ice cream and cookies at every meal!

Now, in fairness, Bill is a perfectly nice gentleman, and his opponent, incumbent Sen. James Sheehan, though an energetic and effective legislator, is not widely regarded as a fiscal prodigy. But really, candidates shouldn't even think they can run with this kind of empty and self-contradictory platform.

Though my exalted peers at publications further up the journalistic food chain balk at taking it on, it is role of the press to call politicians on stuff like this, and here I am, published in newspapers and online. So this is my challenge to you. In mid-October, I'm going to award prizes for the most absurd campaign literature I run across (2008, Rhode Island general election), and I'm inviting your nominations.

Don't submit any just for bad photos or slogans, please. I'm interested in flyers or letters that promise the unattainable or the contradictory. So when some candidate tries to hand you their flyer, take it, and look it over. If you get a candidate letter in the mail, read it, and if you learn about a candidate's web site, go there and check it out. If you think you've found something that can beat my example here, send it in for judging by a panel of impartial judges I'll appoint. (You can send nominations for judgeships, too. After all, vying for judgeships is traditional in politics.) Send your nominations to me electronically, or c/o The Times Newsroom, 23 Exchange Street, Pawtucket, RI 02860. Enter by October 15 or so. May the best candidate win!

02:08 - 20 Sep 2008 [/y8/cols]